I’m a pelvic physiotherapist and, in a fit of temper, I wrote a comedy show about pelvic floors after having yet another woman say to me:

“I’ve been leaking since my baby was born.”

“How old is your baby?”

“He’s 47…”

It is frustrating that people put up with bladder and bowel symptoms which interfere with their day to day life for years. Conditions which we know often respond to conservative treatment. Studies find that between 11-50% [1] people will seek help, the wide variance doubtless due to cultural, social and healthcare system factors. In the UK 15-32% seek help whilst an average of one in three women have symptoms of leakage [1]. Here’s the thing that I just don’t understand – if we know that advice and pelvic floor exercises are effective front-line treatment for incontinence [2], then why do so many women remain wetting themselves? There are more leaky ladies than those who have the common cold!

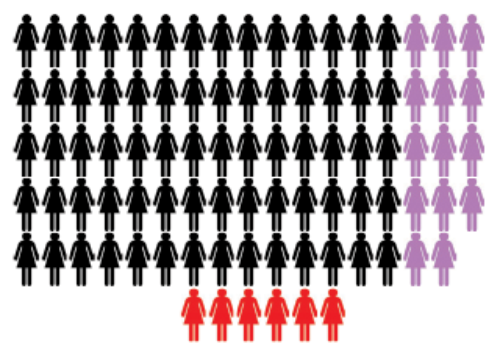

This graphic represents all the women in the world with a pelvic floor.

Those in pink are women who leak.

Those in red represent the few who actually sought help.

In 1998 the World Health Organization stated that incontinence is a largely preventable and treatable condition and “certainly not an inevitable consequence of ageing” [3].

The Continence Foundation of Australia surveyed 130 women who were engaging with antenatal care, and, as part of that, being educated about pelvic health. They found that 2% of them followed the advice they were given [4]. TWO PERCENT! We’re just not getting the message out there and that’s a problem because incontinence trebles the likelihood that women will need antidepressants to treat postnatal depression [5].

The National Institute for Health & Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines state that pelvic floor education should be delivered with antenatal care [6]. In my opinion, based on my own N=1 study, that is flawed. Women who are having their first baby are only really interested in information pertaining to labour and breastfeeding. Pelvic floor exercises will be shelved to the ‘to do’ list. The guideline also means that women who don’t engage with antenatal care don’t get any education. Along with the women who don’t get pregnant. And, obviously, the men. And, people are reluctant to seek help, it takes an average of nearly six years for women to see a healthcare professional about their incontinence [7].

Stress incontinence could be considered a gateway disorder – it can lead to frequency, urgency, and prolapse. Being incontinent won’t kill you, but the consequences of it might. If you wet yourself in the front row of a Zumba class you’re unlikely to go back. Diseases of inactivity kill people. Incontinence is associated with hip fractures – hurrying to the toilet in the middle of the night increases fall risk. A third of people who sustain a hip fracture will be dead within a year [8]. We don’t currently collate figures on how many of these injuries are associated with bladder or bowel urgency. Every older person who presents with a fall should have a multifactorial falls assessment which includes assessing urinary incontinence [9] – but time pressures on busy orthopaedic wards mean that this can often be a challenge. Incontinence is a massive, and under-recognised, public health problem.

The NICE guidelines for urinary incontinence state: “Refer women with UI who have symptomatic prolapse that is visible at or below the vaginal introitus to a specialist” [10]. So, what about the asymptomatic ones? At the moment, there is no standardised prolapse education for women. We wait until the cervix falls out and then refer the patient on for treatment. Fifty percent of women over the age of 50 have a prolapse [11]. Symptoms can be a barrier to exercise, and the numbers of women with pelvic organ prolapse are anticipated to increase by almost 50% by 2050 [12]. The POPPY trial found that even a grade three prolapse could be conservatively managed [13]. Prolapse is common, can often be conservatively managed and is going to become more prevalent with an ageing population, yet women are often unaware that they have a prolapse, or they don’t recognise the symptoms, or they are too embarrassed to seek help. I have looked at every single pregnancy book, magazine, website and podcast I can find, none of them mention prolapse. Education is always a good thing. Especially when it can prevent or manage conditions.

The NICE guidelines [10] recommend doing an internal while teaching pelvic floor exercises to ensure the woman is performing them correctly, to assess power and to check for pelvic dysfunction. Which is great for that one, consenting woman lying there in front of me – but, there are six million leaky ladies out there. I only have two hands. And, to be honest, I’m a bit clumsy with my left hand. It’d take me a while to get round all six million women. There are simply not enough physiotherapists. If we educated women properly through the pregnancy and menopausal years, then perhaps women with uncomplicated cases of stress incontinence could trial self-management, recognise when they need more input and know where to access it.

The costs to the public purse are huge. In 2010, Australia commissioned a review of the costs of incontinence [14]. They didn’t just include the cost of mopping up. They included the cost of people having to move into residential care purely for continence management, welfare payments and loss of earnings. $42.9 billion is a lot of money. Our societies are similar, our health challenges are similar – so, I think it’s reasonable to assume there is a correlation between what the Australians spend and what the UK spends. Supposing 10% of women can accurately self-diagnose and effectively self-manage their stress incontinence? Ten percent of about $43 billion is $4.3 billion. That’s a decent saving for the Australian public purse. And, the value of that saving is immeasurable to the women who, because they are dry, are less likely to be depressed, more likely to be physically active, less likely to break a hip and more likely to have good sexual function.

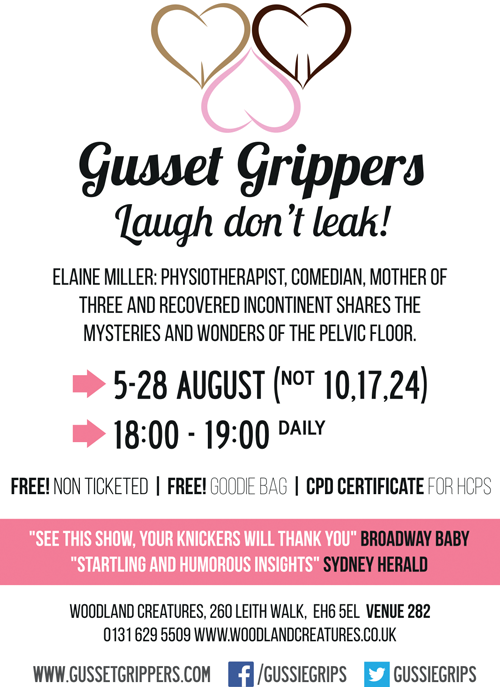

Having poor control of bodily functions quietly disempowers women by interfering with every single thing aspect of their lives. But, how to reach these women? Comedy commonly addresses taboo subjects and I wondered whether delivering pelvic floor education in a non-clinical setting might encourage engagement. If you make socially cohesive groups laugh then they’ll talk. That leads to sharing experiences, gaining empathy, and, hopefully, seeking help. Which was the aim of ‘Gusset Grippers’ – to break down taboos and encourage people to seek help. Can we use humour as a health promotion tool, and to encourage compliance and, how on earth would we measure that? Humour is, by nature, subjective, so is very difficult to research. We could do an RCT with a joke that makes 100% of people laugh 100% of the time and an MRI scanner. I’ve so far been unable to come up with that joke. And, if I did, I wouldn’t want you analysing it – a joke is like a frog, if you want to find out how it works you have to kill it.

Laughter has clear bonding unifying effects and so is a useful tool at breaking down taboos. So, this year, I am going to do the Edinburgh Fringe properly and survey the audience to see whether delivering pelvic education from stage can effect behavioural change. If you come then I will give you a list of references, reflective questions and a CPD certificate. Which is probably the funniest thing about the show…

References

1. Altman D, Cartwright R, Lipitan MC, et al. Epidemiology of Urinary Incontinence (UI) and other Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) and Anal Incontinence (AI). In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A (Eds). 5th International Consultation on Incontinence ICUD-EAU; 2013; page 27-43.

2. National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. NICE pathway - urinary incontinence in women. 2016.

3. World Health Organization Calls First International Consultation on Incontinence. Press Release WHO/49, 1 July 1998.

4. Continence Foundation of Australia (unpublished research).

5. Fritel X, et al. Association of postpartum depressive symptoms and urinary incontinence. A cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016;198:62-7.

6. National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. Antenatal care for uncomplicated pregnancies (NICE guideline CG62). 2008 (updated 2016).

7. Wójtowicz U, Płaszewska-Zywko L, Stangel-Wójcikiewicz K, Basta A. Barriers in entering treatment among women with urinary incontinence. Ginekol Pol 2014;85(5):342-7.

8. Sullivan KJ, Husak LE, Altebarmakian M, Brox WT. Demographic factors in hip fracture incidence and mortality rates in California 2000-2011. J Orthop Surg Res 2016;11:4.

9. National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. Falls in older people: assessing risk and prevention (NICE guideline CG161). 2013.

10. National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. Urinary incontinence in women: management (NICE guideline CG171). 2013 (Updated 2015).

11. Bordman R, Telner D, Jackson B, Little D. Step-by-step approach to managing pelvic organ prolapse. Canadian Family Physician 2007;53:485-7.

12. Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in US women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114(6):1278-83.

13: Hagen S, et al. Individualised pelvic floor muscle training in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POPPY): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:796-806.

14. Continence Foundation of Australia. The economic impact of incontinence in Australia. Deloitte Access Economics; 2011.

Declaration of Competing Interests: None declared.