In this series of articles I am going to show you some of the exhibits contained in the Museum of Urology, hosted on the BAUS website (www.baus.org.uk).

This month I am joined by my friend and fellow member of the EAU History Office, Prof Dirk Schultheiss; we had both, independently, bought the biography of a Victorian urologist and become fascinated by his story.

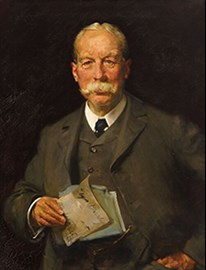

Figure 1: Portrait of George Buckston Browne, by Edgar Bundy, 1915

(by kind permission of the Royal College of Surgeons of England).

On 15 April 1926, George Buckston Browne (Figure 1) became an FRCS, but George was born in 1850, entered University College in 1868, passed his Part One FRCS in 1872 and MRCS in 1874. The old FRCS was known as a hard exam, but 54 years does seem quite a long time; it would appear he took a slightly unusual career path.

George Buckston Brown (1850-1945) was a clever and hard-working man. The fifth generation of a medical and very religious family, he won the gold medals in chemistry and midwifery, the Liston Gold Medal and was made prosector to the anatomy professor. But, when he sat the MB ChB exam in 1872 he failed the chemistry paper (the subject in which he had won a gold medal!). Rather than re-sit the year, he made the career-changing decision to just go for the MRCS; no one without a London MB could expect a hospital appointment in the future.

Nevertheless, he ‘won’ the position of house surgeon to Sir John Erikson (this job interview was a three-day competition) at University College Hospital. It was in this capacity that he met Sir Henry Thompson and furthermore by quick thinking and hard work saved the life of one of his patients.

A year later, when Browne was working as an anatomy demonstrator, Sir Henry Thompson walked into his dissecting room and asked him to be his assistant in his huge London private practice. Giving him 24 hours to think it over, he invited him to give his answer at dinner at Thompson’s Wimpole Street house the next day, Christmas Eve. Buckston Browne agreed and was paid £200 a year and allowed to take on his own private patients.

Buckston Browne continued to study for his FRCS but when he took the exam, he was failed by Mr John Marshall, who said he had tied off a vein and not the brachial artery as instructed. Marshall, according to Browne, hated Sir Henry Thompson and was jealous of his knighthood. Brown felt this was the reason for the fail and never entered the College again until he had retired. But this was another blow and now he had no chance of a London hospital position.

Browne assisted Thompson in his busy practice and cared for his patients when he was away on his long summer holidays or if he was unwell. Despite bringing in thousands of pounds for Thompson in these periods he was not given a single penny over his salary but he did learn much from Thompson, in particular his skill at passing urethral instruments such as the blind lithotrite. Thompson, of course, was famous for having operated on Leopold I of Belgium (Queen Victoria’s favourite uncle). Browne also had the opportunity to meet all the great medical men of the day and came to know most of the doctors in London. This was a great help when, after 14 years working for Thompson, he began to work alone in private practice at 80 Wimpole Street.

From 1889, he worked unceasingly at his practice seeing patients from morning to evening and caring for ‘inpatients’ in various rented rooms around Wimpole Street, all of which he personally unlocked and locked every morning and evening. He never had a secretary, writing all letters personally and took no holiday for 35 years.

Browne was not only an expert with the lithotrite, but probably one of the most skilled at passing a catheter. He used the old way of catheterising men standing and had a ‘stall’ in his rooms with arm rests for the men to stand in. He probably introduced the open suprapubic approach to excision of bladder tumours, although Thompson wrote the book on it, and published many papers on urological conditions.

Amazingly, for a man without a London hospital position and without an MB or FRCS he amassed a huge practice and fortune. In later life, much of this fortune he generously donated to a multitude of medical causes.

In 1919, Browne’s only son died of pneumonia, his grandson died five years later, of typhoid, and his wife passed away in 1926. He was devastated but continued to work hard, this he said being a “mild anaesthetic” to his sadness. With no male heir to carry on the medical tradition (his daughter married Sir Hugh Lett, a urologist at the London Hospital and president of the RSM Urology Section in 1932) he wanted to make use of his money. Already a generous benefactor of the Royal College of Surgeons, in 1927 he offered £5000 to support an annual dinner (to include wine and cigars) for 100 guests at least half to be MRCSs. He endowed a medal, in memory of his son, to the Harveian Society and later a dinner.

Buckston Browne was always a great admirer of Charles Darwin and when, in 1927, he heard that Darwin’s former home, Down House, was for sale, he bought it so it could be preserved as a national memorial to Darwin. He paid £4250 giving another £10,000 for its restoration and a further £20,000 for upkeep. Later, very keen to support the Royal College of Surgeons and maintain a link with research to Darwin’s old home, he donated a further £100,000 to build a research centre for the College adjacent to Down House.

Sir George Buckston Browne was knighted in 1932. He was made a Hunterian trustee and given the gold medal of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. On 15 April 1926 he was made FRCS by election of the council. He failed his MD ChB as a student, then failed his FRCS but he became a well-known and trusted surgeon skilled in urethral instrumentation. He also amassed a fortune with a huge private practice and is still remembered by annual dinners at the Royal College of Surgeons and Harveian Society who award the Buckston Browne medal for presentation of original work every three years.