In this series of articles I am going to show you some of the exhibits contained in the Museum of Urology, hosted on the BAUS website (www.baus.org.uk).

I’ve only recently paid full attention to Sir William Fergusson (1808-1877). He was a famous Victorian surgeon, so well known that he featured on one of the famous Vanity Fair prints of ‘Men of the Day’ (Figure 1). I’d heard the name Fergusson in association with a type of lithotrite but, following some recent research on early prostate surgery, the name came up once again and I began to pay more notice.

Figure 1: Vanity Fair print of Sir William Fergusson, 1870.

William Fergusson was born in Prestonpans, East Lothian, Scotland on 20 March 1808. He was the son of James Fergusson; the Fergussons were the local lairds. He was educated initially at Prestonpans and later at the High School and University in Edinburgh. Initially, he thought his future was in law and at the age of 15 he served as an apprentice in a legal office. After two years he found it was not for him and changed to medicine becoming a pupil to the famous Edinburgh anatomist and surgeon Robert Knox (1791-1862). Fergusson clearly impressed Knox as he was appointed as one of the demonstrators at the famous anatomy school in 1828. It was said that he spent up to 16 hours a day dissecting and became a very fine anatomist.

Robert Knox’s school was very popular and in competition with other schools in Edinburgh (a major European centre of medical education at that time); as well as pupils, the schools were also in competition to get plenty of fresh bodies to anatomise. Unfortunately, this led to the infamous Burke and Hare scandal. A small number of bodies were gifted to the surgeons from the hangman’s noose, but this was woefully insufficient so a trade in corpses sprang up and ‘Resurrection Men’ (body snatchers or grave robbers) looted the cemeteries for recently buried bodies, delivering them to the anatomy schools, through the back door, at the dead of night. William Burke (1792-1829) and William Hare (dates unknown) took the trade one step further by murdering people and then selling their bodies to the surgeons. They were caught. Hare gave King’s evidence and escaped the noose but Burke was hanged and in a wonderful display of Scottish justice, was presented to the surgeons to be anatomised. This happened at the time that Fergusson was working for Knox and he would certainly have known and been heavily associated with the Resurrection Men. Luckily, this infamous scandal never tarnished his future reputation, possibly due to a note written by Burke in his condemned cell:

“Burke declears that Doctor Knox never encoureged him, neither taught or incoriged him to murder any person, neither any of the assistants, that worthy gentleman, Mr Fergison was the only man that ever mentioned anything about the bodies. He enquired where we got that young woman Paterson because she would seem to have been well known to some of the students.

Sined, William Burke. Prisoner. Condemned Cell, Jan 21 1829”

William Fergusson became surgeon to the Royal Dispensary in 1831 and then in 1835 to the Royal Infirmary. At this time in Edinburgh there was another well-known surgeon, James Syme (1799-1870), slightly senior to Fergusson and so potentially holding him back from the top position in that city. Therefore, in 1840 he moved to London to take the Chair of Surgery at King’s; he was 32.

“Hare gave King’s evidence and escaped the noose but Burke was hanged and in a wonderful display of Scottish justice, was presented to the surgeons to be anatomised”

Fergusson, of course, was a general surgeon performing whatever surgery was required in whatever part of the body it was needed (within reason, at that time the deeper recesses of the body were still taboo). His repertoire included of course perineal lithotomy. He was said to be very skilled and very fast; “blink and you’ll miss it,” they said! Writing in 1864 he described a ‘near miss’ during the lithotomy of a four-year-old boy. He almost lost his way and pushed his finger beneath the bladder, realising just in time he extended the urethral incision and reached and removed the stone. His description shows his full understanding of the anatomy, the operation and the honesty required to promote good surgery. Fergusson was a great advocate of conservative surgery, famously recommending excision of the knee joint rather than the easier but ultimately more disabling above knee amputation. In fact he claims to have been the first to use the phrase, ‘conservative surgery’ in this context. In urology, this was expressed by his adoption of the new, minimally invasive lithotrite.

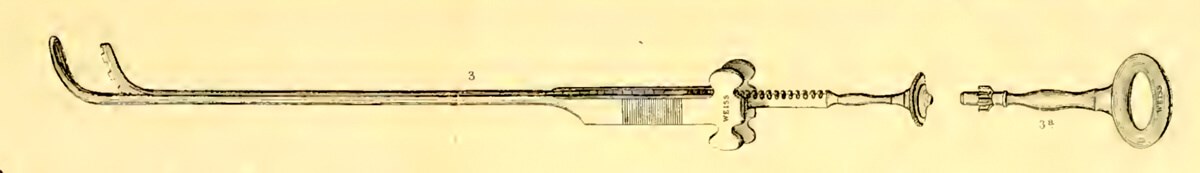

Figure 2: Fergusson’s rack and pinion lithotrite.

Lithotrity, the destruction of stones in situ with an instrument passed per urethra was a procedure which came from France. The ‘Holy Grail’ of stone surgeons, the first working lithotrite was made by Jean Civiale (1792-1867) of Paris in 1824. A multitude of adaptations of this instrument appeared from Civiale and his rivals and contemporaries in the next few years. Fergusson bought a Civiale type lithotrite in the Spring of 1829 in Paris. After some years of use he realised, like many surgeons, that improvements could be made and in 1835 produced his own model. Different to the others he used an ingenious rack and pinion mechanism to generate sufficient pressure to crush the stones (Figure 2). Interestingly, a picture of Fergusson’s lithotrite appeared in a subsequent book by Civiale. It is unclear if this was accidental or deliberate plagiarism, but at the very least it certainly represented a positive review by the father of lithotrity.

The second area of urology where Fergusson’s name appears is in early prostate surgery. Before prostatectomy was contemplated for un-obstruction of the lower urinary tract, the prostate was mainly an organ which got in the way of the lithotomist. Often the surgeon had to cut through the gland to reach the bladder or to extract the stone. In 1848 at a meeting of the Pathological Society of London, Fergusson displayed pieces of prostate gland he had removed during lithotomy for the stone. Rather than this being received positively or at least with interest, he subsequently became aware of “whispers” rumouring his surgery was “rough” and embarrassed, he fell quiet about the subject.

By 1870 Fergusson, now ‘Sir William’ and a much more experienced surgeon, revisited the topic. He suggested in an article in The Lancet, that occasionally, some, or all, of the urinary symptoms of stone sufferers were due to the prostate not the stone. He further suggested that in such cases the enlarged lobes of the prostate, as they fell into the way of the stone extracting forceps, should be pulled or cut out, or enucleated by the surgeon’s finger.

It is clear from his tone that this was still deemed an unusual course. However, based on his experience, he felt he was able to “step out of the suggested course of precedent” and recommend that this be always done when an enlarged prostate was found at the time of lithotomy. Indeed he went further, although an enthusiast of lithotrity and conservative surgery, he wrote that in cases of obviously enlarged prostate open lithotomy should be carried out in the first instance and not per urethral lithotrity.

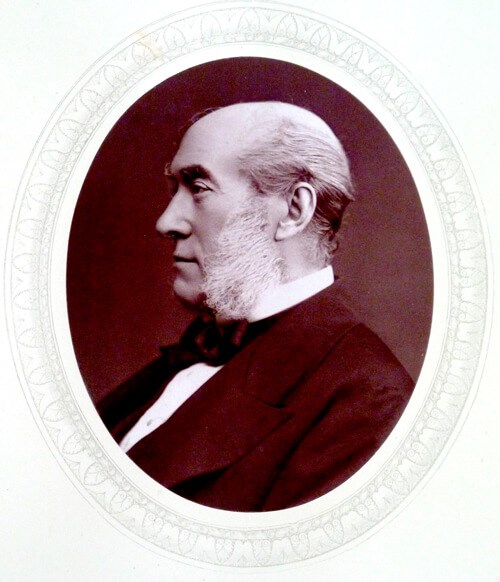

This was not, as we might now think, due to the difficulty of negotiating the instrument through the enlarged gland but to enable primary removal of the prostate. William Fergusson excelled in London. In 1849 he became surgeon to Prince Albert, in 1885 surgeon-extraordinary to Queen Victoria and in 1867 Sergeant-Surgeon. He had been made a baronet in 1866. He became president of the Royal College of Surgeons and the British Medical Association (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Sir William Fergusson, Woodburytype image (an early photograph), 1880.

Sir William Fergusson died on 10 February 1877; 2000 mourners stood on the wintry platform of Euston Station as his body was taken for burial back to Scotland. One of the great surgeon-anatomists, when speed of operating was as important as accuracy in that pre-anaesthetic age, William Fergusson was a promoter of the conservative lithotrity of stones yet was practical enough to realise that the obstructing enlarged prostate also required removal to treat the lower urinary tract as a whole; quite a modern outlook for someone who trained in the age of the Resurrection Men.