In this series of articles I am going to show you some of the exhibits contained in the Museum of Urology, hosted on the BAUS website (www.baus.org.uk).

It’s not often that a urological procedure enters popular culture. This particular one however, appeared in a Sherlock Holmes mystery, was the topic of a novel, the name of a cocktail and got a mention in a Marx Brothers film. The procedure was the grafting of testicular tissue of chimpanzees into the testicles of men and was ‘all the rage’ in the 1920’s.

The loss of virility and sexual power has long terrified men. In Homer’s Odyssey the hero, Odysseus, was warned of the terrible power of the witch, Circe. As the reader (originally the listener) of that epic poem, one would wonder what terrors could rival those of the Cyclops, the Sirens or the gauntlet of Scylla and Charybdis. The answer? Circe had the power to render him impotent! Thankfully, the god Hermes had a magical cure. Over the centuries, doctors have fed men the testicles of a variety of animals to improve their virility; and men have gladly taken them. Even beans, which look a little like testicles, have been promoted as having sex-enhancing properties. However, it was not until 1869 that a doctor began to apply scientific thought to this problem.

Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard (1817-1894) was a famous French physiologist who was getting on a bit. Maybe that was the reason he began experimenting with extract of animal testicles in 1875, injecting this into other animals. In 1889, at the age of 72, he began injecting himself with extract of crushed dog and guinea pig testicles. He told the Société de Biologie in Paris it had increased his mental and physical powers as well as his urine flow and ability to evacuate his bowels!

Eugen Steinach (1861-1944), working in Vienna, was also investigating the testicular function of animals. He found (or he thought he found) that ligation of the vasa of elderly rats led to their rejuvenation. He postulated that a process of negative feedback caused the testicular interstitial cells to produce more testosterone. In 1918, with the help of the urologist Robert Lichtenstern (1874-1952), vasectomy for the purpose of rejuvenation was carried out on a human. Steinach’s ‘autoplastic rejuvenation’ became very popular. It is rumoured that up to 100 academics of the University of Vienna had the procedure, as did Sigmund Freud and the Irish poet, Yeats. Yeats believed it had given him a ‘second puberty’ and many feel his best work was produced in this period.

Steinach’s work was reviewed by the English urologist Kenneth Walker (1882-1966) in 1924. He was very complimentary on the quality of Steinach’s animal experiments, but was unable to comment on the results of the operation in man, due to lack of numbers treated. He noted the unfortunate use of the word ‘rejuvenation’ in Stenach’s initial 1920 paper, which he felt raised extravagant hopes and had led to exploitation by “less reputable members of the medical profession”. The latter, he felt, was the reason it had not been taken up in Britain. Clearly sceptical, a true scientist, he did not completely dismiss it, but called for more data.

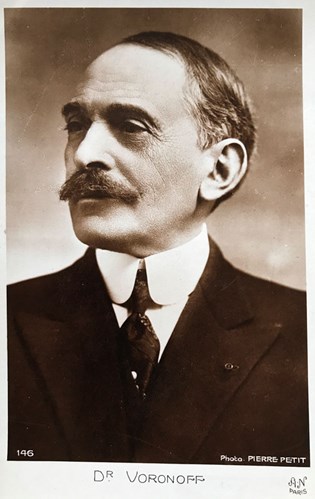

Robert Lichtenstern, the Viennese surgeon who had helped Steinach, was already transplanting testes into patients who had lost their own in the war or following tuberculosis, but it was a Russian surgeon working in Paris who popularised this procedure; his name was Serge Voronoff (1866-1951) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Serge Voronoff (photograph by the Pierre Petit studio, Paris, 1920’s).

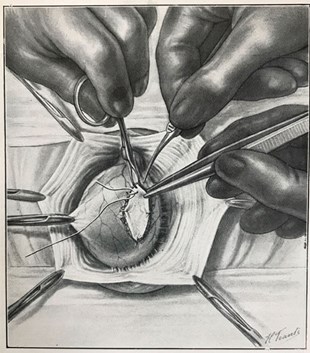

Whilst working in Egypt, Voronoff had observed that eunuchs appeared to age prematurely; he postulated then that testosterone would slow down ageing and began animal experiments implanting testes. On 12 June 1920, Voronoff transplanted testicular tissue from a chimpanzee into a human. Slices of chimp testis were sewn into the recipient’s testicle (Figure 2). Voronoff claimed that the vitalising secretions lasted for up to two years. He presented his technique to the International Congress of Surgery held at the Royal Society of Medicine in 1923. By this time he had carried out 44 cases, six of these were in doctors. His method was supported by Ivor Back (1879-1951), a surgeon at St George’s Hospital. Like Steinach, Voronoff was looking to reverse the ageing process and his clientele were not men rendered hypogonadal by trauma or infection; they were ageing men who sought rejuvenation, vitality and return of their youthful sexual power. It was very popular.

Figure 2: The Grafting of Chimpanzee testicular tissue onto a human testis

(from: Testicular Grafting from Ape to Man, by Serge Voronoff and George Alexandrescu, 1929).

Once again, Kenneth Walker reviewed the technique; in fact he gave a Hunterian Lecture on the topic of rejuvenation in 1925. Although with some scientific restraint, he clearly believed that testicular transplants (in his case not from monkeys but human testes removed due to ectopia) re-vascularised and survived and had a beneficial effect. In 1952, in a book on ageing, Walker, looking back at his work concluded that, “the results of testicular grafting were no better than those obtained from vaso-ligature and probably very little, if at all, superior to the rejuvenation results of our predecessors, the magicians and witches.”

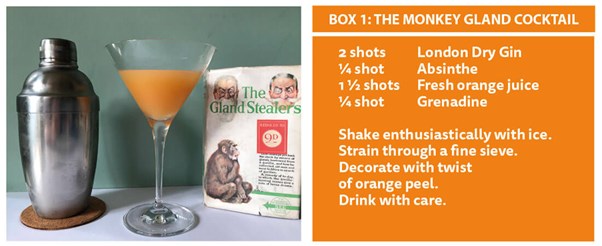

Unsurprisingly, the idea of rejuvenation and the chance to slow ageing, or turn back time, gripped the public and monkey glands began appearing in the most unexpected places. The plot of Bertram Gayton’s 1922 comic novel The Gland Stealers (Figure 3) involves an elderly grandfather being given a new lease of life after receiving implants from Alfred the gorilla and sees him gallivanting off to Africa to find more donors. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who was himself a doctor, used the idea in the 1923 Sherlock Holmes story The Adventure of the Creeping Man, where a scientist injects himself with a rejuvenating potion. In the 1929 film, The Cocoanuts, staring the Marx Brothers, they sing an Irving Berlin song, which included the phrase, “If you’re too old for dancing, get yourself a monkey gland”; the song was called Monkey Doodle-Doo. In Harry’s Bar in Paris, a fashionable new cocktail appeared; ‘The Monkey Gland’ was a potent mix of gin, absinthe, grenadine and orange juice (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Monkey Gland Cocktail and ‘The Gland Stealers’ by Bertram Gayton.

Closer to home, there was some trouble in the English football league, when Wolverhampton Wanderers were accused by Leicester City of cheating by giving their players monkey gland injections. Wolves’ eccentric manager, Major Frank Buckley, allegedly arranged for his players to have injections of what was said to be monkey gland extract. After investigation, the football league did not ban monkey glands, but insisted players only took them voluntarily.

The trend for monkey gland therapy faded away in the 1930’s. It was clearly scientifically flawed, the grafts from animal to man were rejected immediately and injections of testicular extracts contained little or no functional hormone. Testosterone was identified and synthesised in 1935 and this later became a useful treatment for true hypogonadism, if not for rejuvenation of elderly grandfathers off gorilla hunting in Africa!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I am very grateful to Mr PC Butterworth, Consultant Urological Surgeon and amateur mixologist for his cocktail making skills.