In this series of articles I am going to show you some of the exhibits contained in the Museum of Urology, hosted on the BAUS website (www.baus.org.uk).

You might say that genitourinary infectious disease is a part of urology, but allied as we are, you have to admit that GU medicine and GU surgery are often quite distanced. Historically however, venereal diseases played a close and important part in the history of urology.

The first problem we see when discussing the history of venereal diseases is defining them. Now, with the advantage of microbiology and virology we can identify and name the infections that cause sexually transmitted diseases; historically, of course, our ancestors were not even aware they were infections. The three main venereal diseases were syphilis, gonorrhoea and chancroid; lues, gleet and soft sores were some of the names given to them. The inability to differentiate between the diseases meant that healers were unsure if they represented one disease at different stages, one disease that affected different people in different ways or at different times of the year, or separate entities entirely.

The second historical quandary was that syphilis seems to appear suddenly as a terrible plague in the 1490s being absent in Europe before this time. Syphilis was thought to have been brought over by Columbus’ men from the New World. This new disease first reared up during a war; venereal diseases do love an army. When Charles VIII of France invaded the Kingdom of Naples his army quickly marched down Italy taking Naples in February 1495. After the siege was broken it soon became apparent that the invading army, which contained many Spanish mercenaries, had brought with them a terrible plague.

The disease began with horrible genital sores, after a few weeks generalised skin rashes, fevers and agonising shooting pains appeared, these were followed by destructive and extensive ulcers which ate away noses, faces and bones. It was often fatal. It spread like wildfire; it was across mainland Europe by the end of the year and had reached England and Scotland by 1497.

Figure 1: Girolamo Fracastoro. Image in the public domain.

This new and terrible pestilence was blamed and named on the presumed source. The French called it the Neapolitan disease, the Italians returned the compliment, the Russians the Polish disease, the Turks the Christian disease. In England it was the French disease or the French pox or the Great pox (differentiated from smallpox). This syphilis was clearly a much more virulent version than the modern disease we see today, and it was also different to the mild non venereal version seen in pre-Columbian South America. The name Syphilis appears in 1530 in an instructive poem by Venetian physician and poet Girolamo Fracastoro (1476/8–1553 – Figure 1). In a story taken from the Roman poet Ovid, a shepherd called Syphilis blames a God for sending a drought. The God, offended by the blasphemy, sends down a terrible disease on Syphilis. Fracastoro uses the poem to describe the nature and physical appearance of this new disease.

It is unclear if syphilis appeared de novo in the Old World, brought back from the New World by Columbus. There is some archaeological evidence that it might pre-date Columbus. It is possible that they brought back a new strain which manifested itself in a more virulent way to the unexposed immune systems of Europe. Certainly, there is plenty of evidence of penile ulcers, presumed to be venereal in the ancient and mediaeval world. John of Arderne (1307–1392) writing in the 14th Century gives treatments for gonorrhoea or chaude pisse (from the French for hot pee). The burning and swelling he says leads to “huge sorowe and prikkynge”. He recommends urethral injections of a variety of soothing herbs including purslane seed, water lily, parsley, oil of roses or violets, and even the milk of a nursing woman. He also suggests a scrotal support or “lytyll bagge” to prevent further swelling.

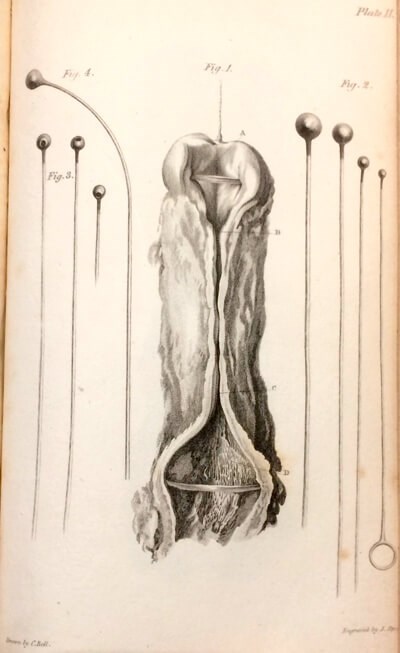

Figure 2: Urethral stricture surrounded by the bougies used to diagnose and treat it.

From Charles Bell’s, Letters on Urethral Diseases, 1810.

Venereal disease causes many urological manifestations, hence historical books on the topic often read like urology textbooks. John Douglas writing in 1737 gives some of the manifestations of the disease including, dysuria, genital sores, priapism, phimosis and paraphimosis, and testicular swelling leading to sterility. A very common consequence of gonococcal infection of course is urethral stricture (Figure 2). In the first half of the 19th Century, Robert Wade (1798-1872) was known for his expertise in treating strictures, an early urology specialist before specialities existed. By the end of that century, Reginald Harrison (1837-1908), also a stricture expert, was headhunted from Liverpool to St Peter’s Urology Hospital in London; genito-urinary surgery by then, had become a recognised speciality.

The first endoscopes were not long or powerful enough to clearly visualise the bladder, however, the Desormeaux (1853) and Cruise (1865) endoscopes (maybe even the Bozzini of 1805), could visualise strictures. Desormeaux and Cruise were the first to operate on urethral strictures under direct vision. Urethroscopes preceded cystoscopes.

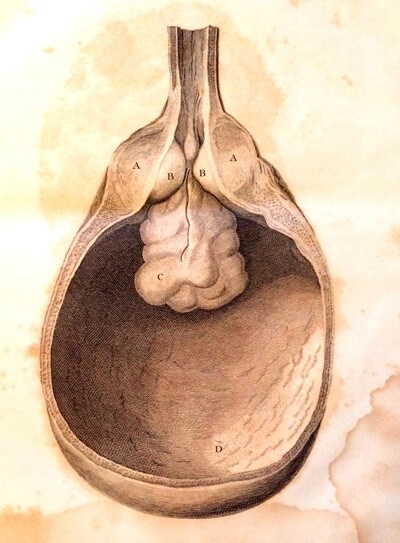

Figure 3: The obstructing prostate, from John Hunter’s book Venereal Disease, 3rd Ed. 1810.

It is in John Hunter’s book on venereal disease that we see the early representation of the obstructing prostate (Figure 3), one cause of prostatic swelling being infective, hence its inclusion, but this also demonstrates the close link between venereology and urology. This association with venereal problems, at best due to loose morals and at worst a direct punishment by God, is said to be one reason that urology in England was so late to be accepted as a speciality. When St Paul’s Hospital, one of the famous three P’s London urology hospitals (St Peters, St Pauls and St Phillip’s), was opened, there was an outcry from the local residents. This was probably due to the huge sign in their square, “For Skin and Genito-Urinary Diseases!” Not only a case of “there goes the neighbourhood” but surely, “there goes the Profession”. Yet, there were many of the ‘new’ urologists of the early 20th Century who were happy to be involved in and associated with the management of venereal disease. Frank Kidd (1878-1934), the founder of the genitourinary department at The London Hospital, believed that no urologist could hope to be successful or even competent unless he was fully acquainted with venereal diseases of the urethra.

The association with a sexually transmitted disease may have been one factor that slowed the appearance of the pure urologist in Great Britain, but it was certainly not the main reason; the urological manifestations of venereal disease might actually be said to have helped develop urology as a speciality. Of course, bladder stones led to the first urology operation and the stone cutters were the first specialists, strictures however led the way in endoscopic surgery before bladder stones did. The desire to visualise the urethra led to the development of better instruments to look beyond into the bladder. Most afflictions of the lower urinary tract can be caused by or mimicked by venereal disease and thus had to be treated or excluded, hence early books on venereal disease or genito-urinary surgery were one in the same. So venereal disease, particularly gonorrhoea (or the running gleet as it was once also called) with its chronic and usually non-fatal destruction of the lower urinary tract had an important part to play in the history of urology.