The General Medical Council (GMC) requires all trainee doctors to carry out Quality Improvement (QI) as part of our annual appraisal process [1]. Exactly what QI projects are and how to get involved is less widely understood. Traditionally surgical trainees focus on research or audit projects.

Every trainee entering core surgical training can recite the audit cycle, knows they need to ‘close the loop’ and is well versed in critiquing a clinical paper; but when it comes to QI the room goes silent. Most of this silence is probably due to ‘fear of the unknown’. We aim to fill that gap and help all trainees to obtain a worthwhile QI project. We describe our experience with a QI project and give specific tips along the way to help you in your own project.

QI vs. audit and research

Think of QI as a continuous process, like lots of small audits back to back. An audit asks the question – How are we performing? Research asks the question – What new knowledge can we discover? QI projects ask – How do we actually improve? In many ways a QI project can be seen as the journey from how we are performing now (as identified by an audit), towards what we know is possible (as identified by research) [2].

Project background

In summary, our project looked at trying to improve the care for emergency urology patients with frailty. Picture a 95-year-old male admitted with urinary retention. Once catheterised (and seemingly treated) it transpires he has been living in poor conditions, has undiagnosed heart failure, renal failure, a medication list so long it hurt to write it all down, and short-term memory problems. It’s likely this man will have a long length of stay with delayed cross-specialty and inter-disciplinary communication adding to the already complex care and discharge-planning process.

What to do a project about?

We’d recommend asking your departmental audit lead first, although this isn’t technically audit they may be aware of an ongoing QI project you can get involved in. There is a pack for supervisors on the Royal College of Physicians website [3].

Failing this, have a sit down and think of what is frustrating during your working day, or ask around the theatre coffee room. Is it nursing staff hounding juniors for TTO’s all the time? Or is it the disagreement between consultants on who should be listed for TURP? Or the delay in getting a medical review for your patients? The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) terms this “finding the pebbles in the shoes of your workforce” [4]. Take one of these, discuss it with your audit lead and go from there. People will be interested in a project that is relevant to their practice, anything to make working lives more streamlined will be gratefully received. Examples of QI projects can be found in the ‘Learning to make a difference’ section of the Royal College of Physicians’ website [3].

Top Tip: Stuck on what to do your QI project on? Grab a coffee and think about common frustrations during the working day. Anything to make working lives more efficient will be welcomed.

In our case, we had an opportunity to work with a geriatric medicine registrar on a year’s funded fellowship in QI. We sat down and brainstormed areas we could look at; targeting patients such as the 95-year-old described above was our final choice.

Quality Improvement methodology

QI projects don’t follow the classic audit steps. Try to think of it as an evolving project. Rather than having a purely quantitative outcome from the start, set something more qualitative that can be backed up with quantitative goals e.g. run a chart of length of stay or reduction in readmissions. Our aim was to “try and improve care for frail emergency urology patients”. Setting yourself an aim such as “to reduce length of stay (LOS) for elderly urology patients by two days” would be setting yourself up to fail. This is not how QI works and you won’t be expected to set aims like this. It’s more important to identify the individual steps in the patient journey which contribute to this – e.g. a delay in a medical opinion, a delay in a TTO or a delay in transport. Once the elements are identified, the process can be targeted with individual improvements around this area.

Before starting we’d recommend reading a summary on QI methodology such as those supplied by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) [5]. We used a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) method. This is probably the most widely understood and used QI methodology available internationally, and will be recognised when you present and publish your work, which you will! This methodology works by planning and then implementing a single change, studying its effect and then moving forward to make another change and so on (Figure 1).

Figure 1: the PDSA cycle.

Our first PDSA cycle was for the geriatric medicine team to see all men over 65 admitted with retention on a daily basis. After a short time, we realised that the focus was wrong and that we should instead focus on older people with frailty, rather than specifying an age cut-off. Our next PDSA cycle therefore saw the geriatricians reviewing all patients who met trust ‘frailty criteria’. Future cycles involved the introduction of a regular ward-based MDT meeting and a urology-specific clerking proforma for older people with frailty.

Depending on your project, QI often involves many healthcare professionals. Communication has been highlighted as the sticking point for many QI projects. Getting to know your occupational therapists, physiotherapists and staff nurses is essential in creating a positive change to your department that can be integrated into everyone’s daily work life. Designing our own ward-based MDT meeting ended up being the key to success of our project. As trainees we move on, but the nursing staff and allied healthcare professionals will stay much longer. Use this as a positive for your project.

Top Tip: People can be apprehensive about changes in their working lives. Get a good rapport with your team, from porters to managers. You will need everyone to engage and pull together to make this work for the department.

How to measure ‘success’?

This can be difficult. Before you begin, remember that within QI circles you are not necessarily expected to achieve defined quantitative results you may get in a research project. Whereas you and the department may feel you are doing well you may find that managers want figures and statistics to grant funding to continue projects.

It’s worth looking at a few outcome measures; below are a list that we looked at:

- Time taken to specialty review – this was reduced from nine days to one day in our case.

- Documentation of co-morbidities – if you can show you have improved this then funding will be easier as co-morbidities are linked to secondary care funding. Our urology clerking booklet improved our average co-morbidities from four to ten.

- Surveys – you can create your own survey easily with online generators. Send to staff in the department for their feedback on the project.

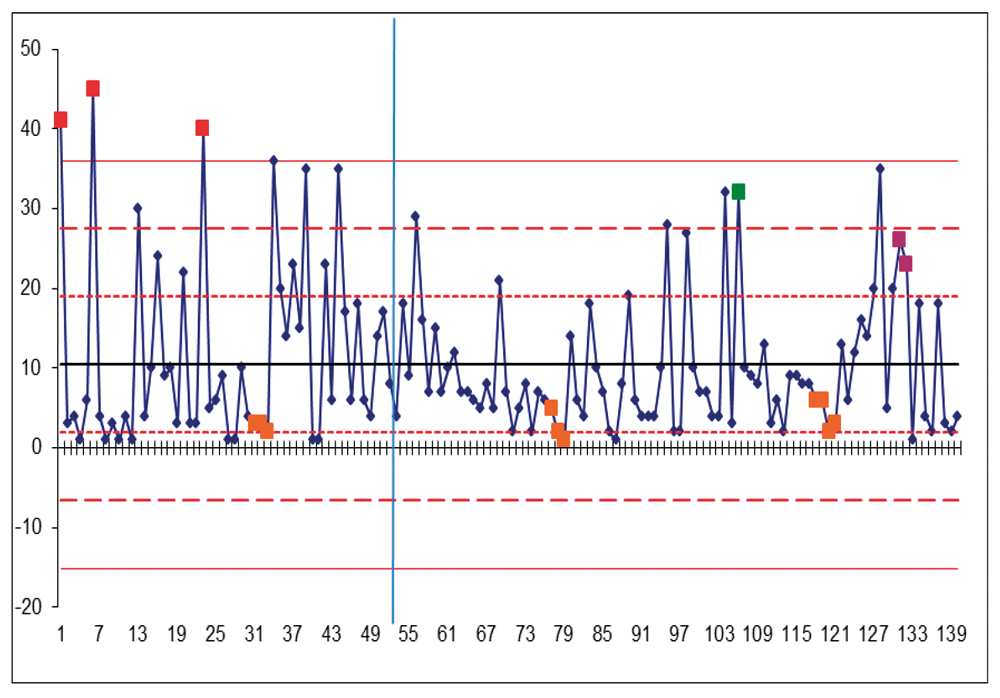

- Length of stay – this can be difficult to impact upon with one project and also tricky to display. Using a statistical process chart (SPC) can help with this.

An SPC represents how a process changes over time. Data are plotted in time order. It has a central line for the average, an upper line for the upper control limit and a lower line for the lower control limit. This allows you to see the trend in your data such as a reduction in variation (as shown in our project). See below for our SPC chart on length of stay (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Statistical process chart of length of stay for the first nine months of the project. Each patient and their LOS is represented by a dot and are plotted in order of time. One and two standard deviations from the mean are shown with horizontal red lines. The vertical blue line represents initiation of MDT and frailty criteria.

Other outcome measures you could consider include:

- Readmission rates – again if you can show a reduction in this then funding will be easier to negotiate.

- Friends and family test – wards are required to do this, collect the data from the ward sister and see if there’s been a change.

Top Tip: Split your outcomes into quantitative and qualitative. Use an SPC chart to show changes in trends.

Project longevity

These projects can take time, in our case 12 months, and the project is still developing. If the project is dropped after a short time then it is likely it will fall by the wayside and all your hard work will be forgotten and won’t continue to help your patients. If you’re on a fellowship year, or have a long time in one trust, this is a good opportunity to do your QI project. Otherwise be prepared to hand it over at the end of your rotation to a fellow trainee, maybe have one in mind that you could discuss the project with to allow for some overlap. Alternatively prepare the department for the project to be handed to them when you rotate, for them to have ownership of it. In our case, it took a dedicated team working on the project intensively for a year but, despite the fact that most of the team members have now moved on, the project is still running strong. You should consider having a senior lead for the project, such as a consultant that won’t be rotating to provide continuity to the project.

Top Tip: You can’t cure the world in one rotation, change takes time and patience. Be prepared to hand over the project when you rotate.

Getting the most out of your project

Of course, we all do this to improve the care we can give to our patients. Alongside that a QI project will add to your professional development considerably. Trainees should link it to aspects of the ‘Professional behaviours and leadership skills’, and ‘Principles of quality & safety improvement’ section of the curriculum for their annual appraisal. It could also be used as your yearly project for discussion at appraisal, you’d be amazed how interested the panel will be in a non-scientific project because of its relevance to their everyday practice. Most national conferences now have a platform for QI (for example, BAUS 2018 had a QI session) meaning you have the opportunity to present your work nationally and internationally. Finally, write your project up into an article. There are now dedicated spaces for QI projects such as ‘BMJ quality and safety’. You will also find QI projects will fit into the ‘article type’ section of most journals. The ‘SQUIRE’ guidelines provide a layout for presenting QI projects and are well recognised (www.squire-statement.org).

Top Tip: Share your experience. You’ll find that other projects are hitting similar bumps in the road as you, brainstorm solutions together.

Urology and Quality Improvement

The Education in Quality Improvement Study (EQUIP) is a research programme sponsored by The Urology Foundation that aims to bring the principles of Quality Improvement into urology training to optimise patient outcomes. This project, led by Professor Nick Sevdalis and James Green, puts urology at the forefront of Quality Improvement implementation and education in the United Kingdom. Future work aims to disseminate Quality Improvement principles, training and resources on a national level. There will be opportunities for trainees and consultants to join this initiative, locally and nationally. Further useful resources and information in regards to Quality Improvement are available at www.kingsimprovementscience.org/home

References

1. General Medical Council. Revalidation.

www.gmc-uk.org/registration-and-licensing/

managing-your-registration/revalidation

Accessed 6 September 2018.

2. Quality Improvement Tips. Step 9 – QI vs Audit – TIPS QI.

https://tipsqi.co.uk/guide-9/

Accessed 6 September 2018.

3. Royal College of Physicians. LTMD toolkits. 2017

www.rcplondon.ac.uk/

guidelines-policy/ltmd-toolkits

Accessed 6 September 2018.

4. Royal College of Physicians. Joy in work: more than the absence of burnout.

www.ihi.org/communities/

blogs/joy-in-work-more-than-

the-absence-of-burnout

Accessed 6 September 2018.

5. Healthcare Quality Improvement Programme. A guide to Quality Improvement methods.

www.hqip.org.uk/wp-content/

uploads/2018/02/guide-to-quality-

improvement-methods.pdf

Accessed 6 September 2018.

Message from Urology News

Please share your experiences of Quality Improvement with Urology News: We hope to include positive and negative QI experiences as a regular feature so that we can learn from each other.

Get in touch with Luke Forster:

E: luke.forster@doctors.org.uk Twitter: @LukeFUrology