Good time management is thought to not only reduce stress, but to improve personal efficiency, service delivery, clinical effectiveness and patient care. It was Benjamin Franklin in the 18th Century who originally made the link between success and the proper usage of personal time; stressing that “time is money”. This concept is just as important today and good time management is an essential skill that all urologists must possess. This article aims to increase self-awareness of time management at the same time as considering practical strategies to plan and prioritise effectively in order to achieve a healthy work-life balance.

Background

The measurement and management of time is not a new idea; indeed the measurement of time can be traced back to pre-16th Century BC when there was a primitive cyclic understanding of time such as seasonal changes, sunrises and sunsets. St Benedictine Monks emphasised and encouraged scheduled activities at all times in the 6th Century but it was the Industrial Revolution in the 18th Century that encouraged a focus on efficiency and effectiveness. Letts introduced the world’s first commercial diary in 1812 and the first time management book was published in 1958 written by James Mckay. Since then there has been a plethora of articles, books and available courses to improve the skill, but it does lack a theoretical model.

It has been defined as: time analysis, planning, goal setting, prioritising, scheduling, organising and establishing new and improved time habits [1]; although real examples are likely to embody several of these elements.

Work-life balance

Self-help on the NHS website suggests that the aim of good time management is to achieve the lifestyle balance that you want [2]. Work-life balance “is achieved when an individual’s right to a fulfilled life inside and outside paid work is accepted and respected as the norm, to the mutual benefit of the individual, business and society” [3]. Potential benefits of a good work-life balance not only affect the individual but also the organisation where they work, since there is likely to be a reduction in sickness absences, a more positive work culture and improved recruitment and retention.

Benefits would include improved job satisfaction, greater satisfaction with family life and health, yielding more energy and enthusiasm within the workplace, which can create a favourable impression of you as a competent urologist. In general urologists appear to be quite proficient at this. A recent American survey of physician satisfaction across a range of extra-curricular activities which included a specific 'happiness score' (those questioned were asked to rate their happiness with life outside of work), rated urologists as the third most happy (behind rheumatologists and dermatologists) [4].

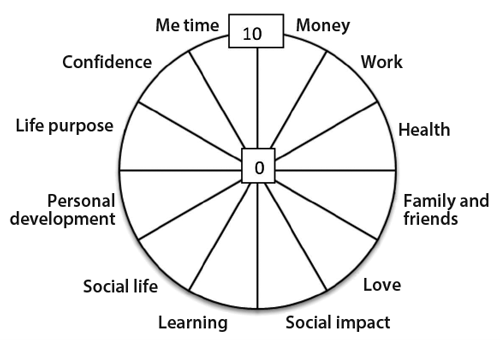

An exercise that can help balance the multiple needs we have in life is the ‘wheel of life’ personal development tool. It creates a visual representation of the balance one currently has in life and comprises twelve sections.

The wheel of life

Instructions

- Imagine a scale from 0-10, with a 0 at the centre of the circle and a 10 at the periphery of each segment.

- Grade your current level of satisfaction with each segment by drawing a dot to create a new outer edge, then join each dot up to create a new perimeter. If you are very satisfied with a particular area of your life it would be rated 9 or 10 out of 10; if there are areas of your life where you have not accomplished what you want or it is not bringing the satisfaction you hoped for, give it a lower rating.

- The new perimeter of the circle represents your current balance wheel.

Guidance notes

- ‘Social impact’ refers to the extent to which you are a part of, and exert an influence on, the community around you.

- ‘Learning’ is the acquisition of knowledge for the sake of learning and discovery; what subjects, beyond urology, interest you in your spare time?

- ‘Personal development’ refers to how much time you spend reflecting and developing yourself as an individual.

- ‘Life Purpose’: Do you have a purpose or goals in life or a vision for what life is about? What does life mean to you?

- ‘Confidence’: How do you feel about your own self-worth and confidence?

- ‘Me time’ is time spent relaxing on one's own as opposed to working or doing things for others; it is an opportunity to reduce stress or restore energy

Reflective questions

- What did you score and why? It is often revealing to see which areas are low scoring and which are high as they are not always what you expect; scores change over time and it can be helpful to repeat the exercise again in the future and reflect on any differences.

- Which segment, if improved by one or two points, would also lead to improvements in other areas of your life? This question prompts you to consider the synergistic nature of the various aspects of your life and where best to focus your energies.

Ask yourself:

- How much time am I spending on this area of my life?

- How much time do I want to be spending?

- What do I need to do to improve this area of my life?

An essential skill

Not only is time management a desirable quality to possess, it has also been recognised as an essential skill for doctors. When the Medical Leadership Competency Framework [5] was first developed, junior doctors commented that time management was one of the three skills they most needed to improve. The framework offers advice on developing personal qualities and managing yourself and suggests doctors should “plan their workload and activities to fulfil work requirements and commitments, without compromising their own health.”

There are courses available through the British Medical Association, corporate companies such as ISC Medical’ and local deaneries; but surprisingly little online advice or resources through organisations such as the British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS). Even the General Medical Council (GMC) does not have specific guidance on time management – although if following the document Good Medical Practice (2013) it is easy to see that you need to have good time management skills in order to conform with the standards set out by the GMC universal to all doctors [6].

Enhancing management of time – ‘lean management’

Lean thinking was developed in the world of industry and has been adapted as a service improvement technique in healthcare. By adopting a lean management approach to working we must identify and eliminate wasted resources and, especially, wasted time. Everyday activities can be split into three main categories:

- Value-adding (activities that transform the service you deliver in order to meet the needs of your patients).

- Non-value adding (activities that take your time and resources but do not add any value to the services you provide in the eyes of the patient).

- Necessary non-value adding (activities that have to be carried out because they enable a value adding activity or because of statutory requirements).

Waste is therefore any activity that is non-value-adding and thus a poor use of your time; for example, waiting for people, documents, responses or staff movement, unnecessary movement or travel whilst at work. This can work on both an individual and organisational level.

The need to improve quality and deliver more efficient care has never been greater in the NHS. All organisations must achieve value for money and deliver the best possible care for patients. Before it was closed, the Institute for Innovation and Improvement developed a set of modular improvement programmes that centred on the concept of lean management. The Institute provided assistance in bringing together multidisciplinary teams in order to explore opportunities to improve integrated care by transforming the way we work via a cultural change. One example was ‘The Productive Operating Theatre’ which focuses on quality and safety, and was designed to help theatre teams to work more effectively together and to, amongst other things, improve the effective use of theatre time. For example, in the first 12 months of implementing The Productive Operating Theatre, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust saved £2 million through reducing waiting lists [7,8].

Personal approaches to time management / organisation of a to-do list:

Time management skills can only develop in parallel with other management skills such as assertiveness, priority setting and delegation. Irrespective of prevailing employer and economic demands, all urologists need to use the time they have in the most productive way. Many people keep a to-do list to help manage their work. They following examples can be used to help prioritise and create an action plan:

Approach 1

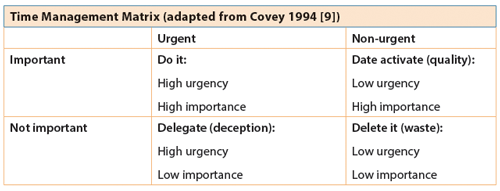

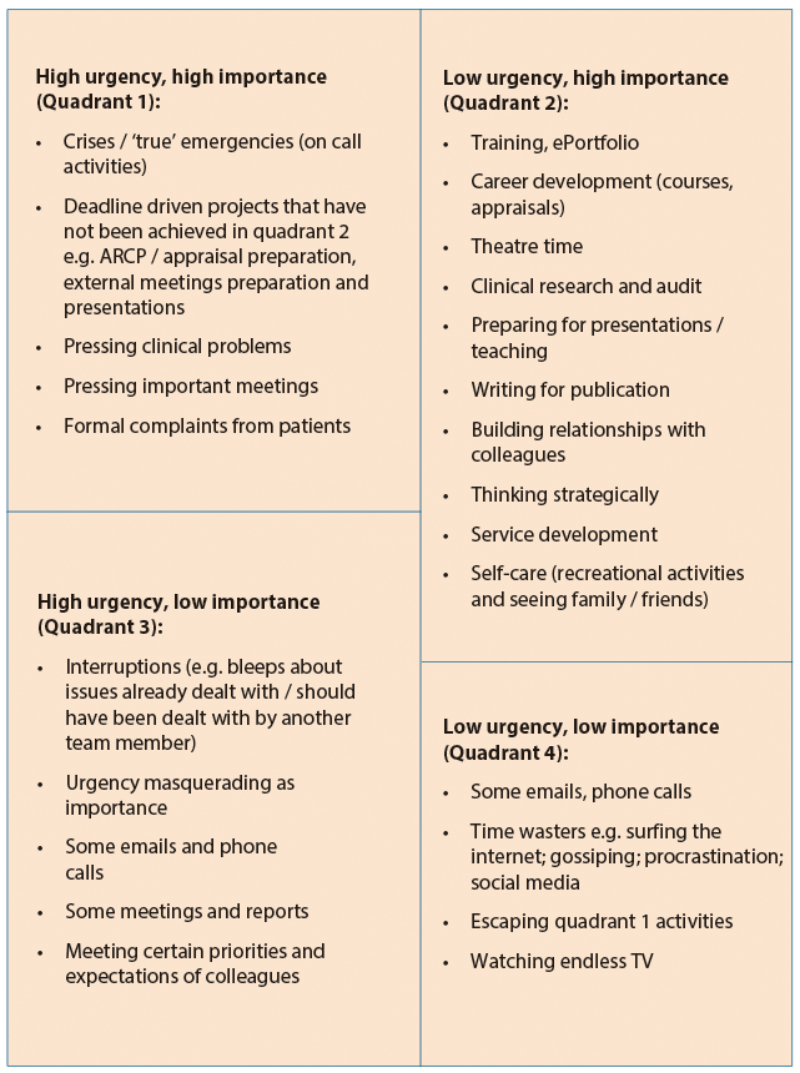

President Eisenhower developed a personal time-management system in the 1950s that divided tasks into four categories:

- Urgent-important items were dealt with immediately.

- Urgent-unimportant items were delegated.

- Not urgent-important items were entered into a calendar.

- Not urgent-unimportant items were minimised or eliminated.

This was later adapted by Stephen Covey [9]. By considering the urgency and importance of a new task, we can theoretically place it into one of four quadrants (and thus allowing us to prioritise our work). Having sequenced your tasks into order of priority, you must make a commitment to action them.

We have adapted this time management matrix for a urologist. Consultants and trainees who spend the majority of their time working in quadrant 1 face burn out as they lurch from managing one crisis to the next. The most effective people stay out of quadrants 3 and 4 and reduce the amount of time they spend tackling projects in quadrant 1. They optimise the time that they spend working on quadrant 2 topics which help them gain control and balance in their lives.

"Time management skills can only develop in parallel with other management skills such as assertiveness, priority setting and delegation."

Approach 2

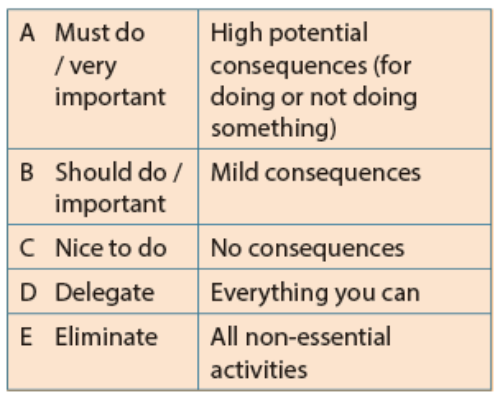

Another example of an approach to organising a to-do list is ‘The ABCDE’ method.

Place one of the following letters next to each task on your list before you begin to work. If necessary, rank tasks that fall within the same category in order of importance e.g. A1, A2, A3, etc.

ABC approach to time management

- Be assertive and learn to say no! (Ask yourself whether this task would help me fulfil requirements of my job plan?)

- Avoid procrastination.

- Batching (dedicate blocks of time to similar tasks e.g. emails).

- Comparative advantage (assign, delegate, outsource or have someone else do any job that can be done at a salary less than you earn).

- Decision making – make them quickly, as soon as the issue arises.

- Delegate all tasks that are not value-adding to you (but always agree when the task will be completed and to what standard).

- 4 ‘Ds’ of decision making:

• Does this task need to be done? No – Delete it.

• Do I need to do it? No – Delegate it.

• Do I need to do it now? No – Date-activate it (put it in your diary for completion at a future date).

• Do it now – by definition, if a task has arrived at this point it needs to be done now. - Electronic diaries – use only one. An electronic one (shared ‘Outlook’ one which synchs with a PDA / smartphone might be useful to give access to colleagues / secretaries).

- Energy peaks – work on your most important or difficult tasks at your energy peaks (i.e. the time of day when you are most alert and awake). For example, writing a report at night could take twice the time than if you were to wake up early.

- Marginal gains – if you improved every area related to your life by just 1%, those small gains would add up to remarkable improvement. Almost every habit that you have, good or bad, is the result of many small decisions over time.

- Pareto principle – also known as the 80:20 rule; 80% of your time-devouring activities are generated by 20% of the causes (usually people or unresolved problems / situations); in these cases it can be highly rewarding to invest time in addressing a situation e.g. having ‘the difficult conversation’ with the person who always interrupts you or sends an inordinate amount of useless emails. Pareto is also relevant to delegation; it may pay to invest time in training / developing someone else to do some of your tasks.

- Plan each day in advance.

- Prioritise – how you spend your time; repeatedly ask yourself: “what is the most valuable use of my time right now?”

- Salami principle – cut big projects into slices. If you ‘eat’ the slices one by one, you will eventually consume the whole salami (in other words, if you set yourself small manageable tasks so that by progressing through them you will eventually accomplish the large task).

- Six P rule – Proper Prior Planning Prevents Poor Performance; failing to plan is planning to fail.

- Ten minute rule – work on a particular task for a maximum of 10 minutes and stop when the time limit is up; this can help limit the resistance to starting a task and help focus the mind.

- Time log – consider completing a consultant job planning diary

(a copy can be found at www.consultantscommittee.info).

Ask yourself:

• What am I doing that doesn’t really need to be done?

• What am I doing that could be done by someone else?

• What am I doing that could be done more efficiently?

• What do I do that wastes others’ time? - Transition time – refers to time spent commuting or waiting and is an invaluable resource for answering emails (if technology allows), reading, planning and reflecting.

- Touch each piece of paper once.

- Workspace – an organised and clean workspace can increase productivity.

Conclusion

As urologists there are many competing demands on our time and it is becoming more important than ever to have good time management skills. Hopefully in this article we have provided a number of strategies that will help deal with increasing time pressures. Implementing one or two of these techniques into your daily routine may be beneficial in helping you use time more efficiently and gain a better work-life balance.

References

1. Hellsten L. What do we know about time management? A review of the literature and a psychometric critique of instruments assessing management. In: Stoilov T (ED.). Time Management. InTechOpen; 2012.

2. NHS time management tips.

http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stress

-anxiety-depression/pages/time

-management-tips.aspx

Last accessed June 2016.

3. The Work Foundation.

http://twfold.theworkfoundation.com/

difference/e4wlb/definition.aspx

Last accessed June 2016.

4. http://www.medscape.com/

features/slideshow/lifestyle/2012/public

Last accessed June 2016.

5. Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Medical leadership competency framework: enhancing engagement in medical leadership. 2nd ed. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement; 2009.

6. General Medical Council. Good Medical Practice. 2013.

7. Institute for innovation and improvement.

www.institute.nhs.uk/quality_and

_value/productivity_series/the_productive_series.html

Last accessed June 2016.

8. Lean thinking in healthcare.

www.institute.nhs.uk/building

_capability/general/lean_thinking.html

Last accessed June 2016.

9. Covey S, Merrill AR, Merrill RR. First Things First: To Live, to Love, to Learn, to Leave a Legacy. New York, USA; Simon and Schuster; 1994.

Declaration of Competing Interests: None declared.