Every year about 6000 men in the UK undergo radical prostatectomy (RP) for treatment of prostate cancer [1]. Despite surgical advances, RP continues to be associated with significant side-effects including urinary incontinence (UI) [2]. Immediately following removal of the urinary catheter, leakage can be sudden, heavy and persistent requiring immediate recourse to continence products.

Most men become dry within a few weeks or months but for a proportion, UI persists and becomes a lifelong health issue that can lead to social isolation and depression. The prevalence of long-term UI (>12 months) varies widely with a conservative estimate of 14% [2].

For most men their first experience of urinary incontinence is after their catheter is removed. Suddenly they are thrown in at the deep end and have to rapidly learn the complex and demanding skills of continence management. Novices in the pad department, they do not know how or where to buy products which seem mostly aimed at women or babies. Lacking in handbags in which to place products, even the simplest outing in a car can seem like an intrepid expedition into an unpredictable world. As for taking any exercise, playing squash or doing gardening these seem impossible when they just make incontinence worse.

“[You] stare at a row of products designed for children and toddlers having no real idea of what size they might be until you buy them.”

Men’s experiences with incontinence

In a recent series of interviews with men (mean age 68 years; range 45-77 years) up to 18 months post RP, we explored the extent of some men’s difficulties with UI [3]. A typical scenario at the point of catheter removal is that men are sent home with a few pads to manage alone. Some will have light leakage, quickly regain continence and require only small pads of the sort available in the supermarket. For others incontinence can be heavy, unpredictable and persistent. With an expectation that men will gradually regain continence, they are neither referred to, nor usually eligible for pad supplies from the limited resources of community-based continence services.

Men’s stories reveal the extent of their challenges with UI, and quotes are shown below. Some are shocked at the frequency and amount of incontinence and the difficulties they face when seeking information and support:

“The help, basically, has been non-existent . . . being pushed from pillar to post, nobody has suggested they might help us.”

UI has a profound impact on men’s lifestyles:

“. . . I haven’t been able to play golf for 18 months because it’s [leakage] stress related.”

“. . . You are very self-conscious about going on public transport – that’s how I feel, I always feel that if anything has leaked and I stand up and I’ve got to walk down through a bus and everyone will be like – oh look at him.”

“If I go anywhere I take a rucksack with me with a clean pair of trousers, underwear, incontinence pads, baby wipes and things like that . . . I have to think to choose a shop that has toilets near the entrance so I can park, rush in . . .”

Self-blame and even regret at treatment choices is not unusual:

“. . . because of the incontinence side of it that is what makes you wonder and it’s always in there niggling away at you, should I have had radiotherapy? If I’d had radiotherapy . . .”

“I just said I can’t go on like this where I’m just peeing because I just wouldn’t be able to do anything. That’s when it impacted on me the most.”

“If the choice is: you are what you are today or I’ll put your prostate back with the cancer – which do you want? I’d say ‘I’ll have the prostate back please’.”

Men’s concerns about catheters

The interviews added to our understanding of the experience of managing post-RP incontinence. A persistent theme was a ‘lack of preparation or support’ and, in particular, concern and fear about ‘having a catheter’; one man said:

“. . . that frightened me to death that thing.”

The participants were unanimous in their recommendation of easy access to a healthcare professional (HCP) and to other men with similar experiences. They stressed that accurate information in a variety of formats would be beneficial in helping to decrease feelings of isolation and anxiety and could improve their quality of life.

Men need effective continence management products from the moment the catheter is removed and throughout the time they are incontinent. Access to a selection of appropriate products and information about how to choose the most appropriate products for their needs is essential to aid a return to an active and fulfilling life. Unfortunately both access and information are often lacking.

“. . . What I’ve found is that if you’ve never experienced anything like this before then it is easier I think to go out and buy a super yacht than to buy pads.”

A Movember and Prostate Cancer UK initiative

In 2014, the Continence & Skin Health research team from the University of Southampton embarked on a programme to develop continence resources for men undergoing RP. Part of the Movember-funded TrueNTH global programme (led by Prostate Cancer UK in the UK) addressing the wider needs of men surviving prostate cancer, the aim of the programme is to provide men and HCPs with a co-ordinated, multi-component resource including web-based information to prepare men for having a catheter and managing UI and skills / tools for informed product selection and optimisation of product use.

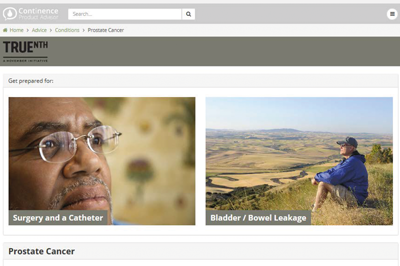

Figure 1. Prostate Continence website homepage.

Web-based information is provided in two ways through:

- A new Prostate Continence Website (PCW, www.prostatecontinence.org – Figure 1) which is part of the existing Continence Product Advisor below.

- New resources for men in the Continence Product Advisor (CPA, www.continenceproductadvisor.org) which is an International Consultation on Incontinence (ICI) and International Continence Society (ICS) collaboration. The content is based on Chapter 20 of the ICI publication Incontinence [4.] The website is hosted by the ICS whose web-team built the site.

Together with men as Public Patient Involvement representatives, the research team crafted the resources which comprise the following:

Figure 2. Example video of how to use a product.

Products

A searchable directory containing comprehensive, evidence-based information about all product designs available to men (and women) including:

- Videos of men using a range of products (Figure 2);

- A supplier database with links to suppliers of different product types;

- Illustrations of products and photos of products in use;

- User tips based on men’s extensive experience of product use

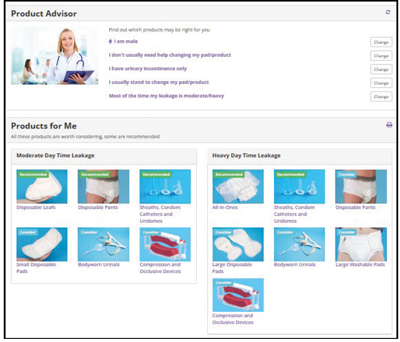

Figure 3. Product Advisor tool.

Advice

Information about selection and use of products to meet individual needs:

- A validated product advisor tool for choosing combinations of products to suit physical needs, lifestyle activities and personal preferences (Figure 3);

- Information about using products for different circumstances e.g. when travelling.

“Access to a selection of appropriate products and information about how to choose the most appropriate products for their needs is essential to aid a return to an active and fulfilling life.”

Prostate cancer-specific product information

Information for men when preparing for:

- Managing a catheter in hospital and after discharge, and preparing for catheter removal;

- Managing incontinence in the short-term after catheter removal and in the long-term if UI becomes intractable;

- Videos of men describing their experiences;

- Illustrations of catheters with a video showing balloon inflation / deflation – something men report they are very worried about;

- A series of PDFs about catheter care (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Example PDF.

How does this resource help men?

Having developed these new and improved resources, we evaluated them with 12 men none of whom had been involved in the development phase. They all had current urinary incontinence or recent experience following RP. All men indicated that they found the websites to be helpful and would recommend them to others. They would have appreciated the information before surgery, when managing their catheter and incontinence at home and when preparing for catheter removal. Men agreed that having comprehensive information in one place and in a user-friendly format would have helped allay fears about what to expect after surgery:

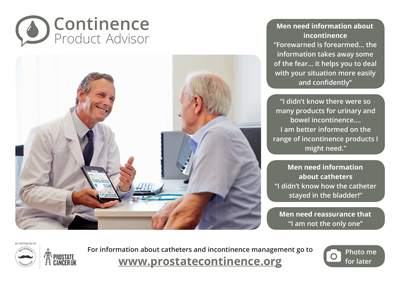

“Forewarned is forearmed and the information contained takes away some of the fear and allows you to think about relevant questions you might need to ask. It helps you to deal with your situation more easily and confidently.”

“Reassurance that I am typical.”

“I didn’t know there were so many products for urinary and bowel incontinence. I hope I won’t need them – I had a prostatectomy and am mainly over incontinence but I will need radiotherapy and I am better informed on the range of incontinence products I might need.”

Helping HCPs to help patients – recommendations

From our interviews with men, it is clear that incontinence remains a poorly understood subject which men are often reticent about reporting. It is therefore essential that patients are routinely asked about their continence. Following these recommendations should help men to feel supported and enable them to obtain appropriate treatment for their incontinence and manage it effectively:

- Before men go home consider signposting them to the Prostate Continence website to help with catheter management.

- At each visit, ask men about their continence status – if they use a pad they have at least some incontinence that requires treatment and / or optimum containment.

- Ensure men understand they are not alone – many other men also have incontinence.

- Check that men understand there are many types of products available to them – pads are just one type and a mixture of different products is likely to be best.

- Signpost men to the Prostate Continence website – Click on www.ics.org/prostateposter to download this A5 card (Figure 5) to help keep the website details to hand.

Figure 5. Prostate Continence website flyer.

“Before men go home consider signposting them to the Prostate Continence website to help with catheter management.”

References

1. Constable L, Cotterill N, Cooper D, et al. Male synthetic sling versus artificial urinary sphincter trial for men with urodynamic stress incontinence after prostate surgery (MASTER): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2018;19(1):131.

2. Milsom I, et al. Epidemiology of urinary incontinence (UI) and other lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and anal incontinence (AI). In: P Abrams, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A (Eds.). Incontinence 6th Edition International Continence Society; 2017.

3. Hislop Lennie K, et al. Understanding men’s experience of urinary incontinence post-prostatectomy. Abstract at IMechE Incontinence: The Engineering Challenge. London, UK; 2017.

4. Cottenden A, et al. Management using continence products. In: P Abrams, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A (Eds.). Incontinence 6th Edition International Continence Society; 2017.

Declaration of competing interests:

This work was funded by the Movember Foundation in partnership with Prostate Cancer UK as part of the TrueNTH programme. Acknowledgements: The ICS IT team who built and maintain the websites – D Turner, R Blackmore, A Brooks, R Lewis; A Cottenden (ICI website editorial team); KN Moore and C Murphy for manuscript assistance; and all the men who have assisted with the development and evaluation of the websites.