The Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT) programme is the largest and most comprehensive initiative to improve the quality and efficiency of individual clinical services that the NHS has ever instigated. The programme falls under the auspices of NHS Improvement and covers all of the hospital specialties; it is also being piloted in general practice.

The methodology underpinning GIRFT is, in essence, simple. As much data about an individual clinical service’s workload and performance is collected from all the available national data sources. This is presented to the relevant trust management team and clinicians in the form of a data pack which benchmarks the department against all of the other departments in the country. Each department is then visited by an experienced clinician (the GIRFT specialty clinical lead) who chairs a meeting of senior trust managers and the specialty’s clinical team.

They review the department’s data as the basis of a wide-ranging discussion which looks at the way that the department is functioning, both celebrating successes and acknowledging challenges. After the meeting, a feedback report is produced which summarises the outcome of the department’s GIRFT review and makes suggestions for service development.

In urology, 134 clinical visits have been carried out, encompassing all of England’s urology departments. Carrying out those visits provided me with a unique insight into the state of play in the country’s urology units. The output from the data collection exercise and the clinical visits led to the publication of a national GIRFT report on urology in June 2018 [1]. Strong support was provided by both the British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) and the British Association of Urological Nurses (BAUN) who contributed to the preparation of the national report and ensured that it was written with the benefit of a wide clinical perspective. The wider GIRFT team provided important input with analysis of clinical data and, in particular, information about procurement costs and litigation expenditure. The report contains 18 core recommendations.

“Perhaps the most ambitious recommendation, but also potentially the most important, is the proposal to establish a national arrangement of urological area networks.”

While the GIRFT programme is an important potential driver of quality and efficiency improvement, it has to be recognised that urology is a rapidly evolving specialty, and that there are numerous examples of ways in which patient care is improving and of innovative good practice already in place. One of the tasks of the GIRFT programme is to identify excellence and help to disseminate effective innovation.

The GIRFT programme in urology has now reached the point where it is time to implement the findings from the individual department reviews and the recommendations from the national report.

The foundations for implementation

Firstly, there is an expectation that all urology staff will have had the opportunity to review their department’s data pack and the post-visit feedback report. These documents will give the clinical team and trust management a steer with regard to the ongoing development of the urology service. Secondly, it is anticipated that all urologists will have reviewed the national report and its recommendations. With all of this information to hand, it should be possible for clinicians and managers to recognise those areas of strength within their urology service and those areas which require further development and offer potential avenues for quality improvement. It is inevitable that there will be a range of issues to be dealt with; longer term aspirations will also emerge. With an agreed agenda, teams will need to establish a programme for project managing the development process.

One of the findings from the GIRFT clinical visits was that there is a minority of urology departments which are failing to deliver good performance and where prospects for improvement appear poor. Problems can arise because of external constraints, such as a very large mismatch between demand and capacity, overstretched trust management, or a lack of leadership skills within the clinical team itself. It is unrealistic to expect good progress in these failing departments without some targeted external input. One of the challenges to the GIRFT programme is to identify clinical services with deep-rooted problems and develop methods for helping such units get back on track.

Implementation: key clinical issues

The GIRFT process has identified a number of areas where patient care is often suboptimal, but where that standard of care has become accepted as business as usual. There is an expectation that urology as a whole will look at the way care is delivered in these areas and ‘reset the dial’. Urology departments will need to look at these areas of practice and prioritise improvements in their clinical pathways.

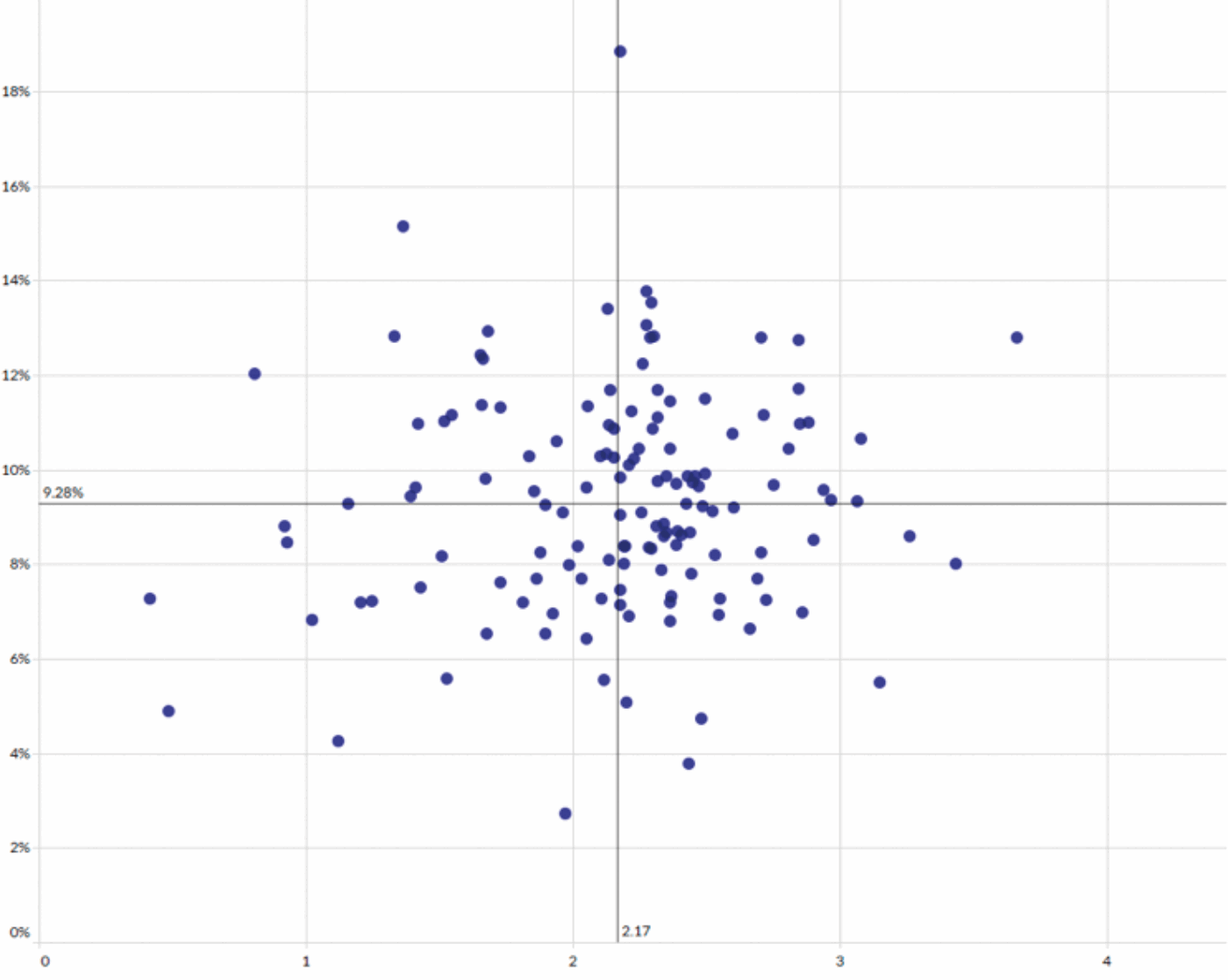

Figure 1: Relationship between length of stay (x axis, days) and 30-day readmission rate (y axis) for patients undergoing male bladder outflow obstruction surgery.

Examples of such areas include:

- The management of male patients admitted with urinary retention. For men who are admitted with urinary retention, and subsequently require surgical treatment, pathways are often excessively long, leading to very symptomatic or catheterised patients having to wait months for resolution of their problem.

- Day case prostatectomy for male bladder outflow obstruction. GIRFT has identified large variations in the average lengths of stay and 30-day re-admission rates for patients undergoing bladder outflow obstruction surgery (Figure 1). There is no clear correlation between lengths of stay and re-admission rates, suggesting that it is possible to achieve good surgical outcomes with short lengths of stay. Many departments have started to embrace new technologies which should routinely deliver safe day-case prostatectomy; such care should become standard practice.

- Improving the management of patients admitted as an emergency with a urinary tract stone. Data collection and information from the clinical visits indicates that for many departments insertion of a ureteric stent is the mainstay for managing patients with upper urinary tract stones who present as an emergency. In the large majority of such cases, there would have been no clinical contraindication to undertaking definitive stone treatment, either with extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy or with ureteroscopy. Resetting the dial in this case involves a change in mindset which is based on the assertion that it is inappropriate not to offer definitive stone treatment for organisational and logistic reasons.

- Delays in providing potentially curative treatment for patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer. It is apparent that the standard where the 62-day stop clock occurs when a patient undergoes a transurethral resection of a bladder tumour is potentially detrimental to patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. For them, the resection is diagnostic, rather than a curative intervention, and they are not benefitting from the additional scrutiny that cancer targets provide. There is a need to ensure that there are no inappropriate delays in the pathway between referral and definitive treatment for patients who present with muscle invasive bladder cancer.

Implementation: other departmental issues

There are a number of other important issues, flagged up through the GIRFT process, that deserve consideration by trusts’ clinical and managerial teams.

The national report emphasises the huge contribution that is now made by urology specialist nurses in the delivery of urological care. However, there is a need to ensure that specialist nurses are undertaking roles for which they have received appropriate training and which are supported by satisfactory governance arrangements. Departments are urged to ensure that nurses are receiving the support they deserve and to ensure that they are carrying out work which allows them to make use of their specialist skills. It is clearly inefficient to have high grade members of the nursing team undertaking tasks which could be carried out by less qualified personnel.

There is an opportunity for clinicians working in trusts that do not have designated urological investigations unit (UIU) facilities to press for the establishment of such units. The GIRFT report makes the specific recommendation regarding the establishment of UIUs on the basis that co-locating urology outpatient investigations and procedures offers the opportunity markedly to improve efficiency, and provide flexibility in service delivery.

A great deal of discussion took place during the clinical visits about the way in which consultants are contributing to the care of patients who are admitted as urological emergencies. The direction of travel is clearly towards on-call arrangements that ensure that consultants are providing hands-on leadership of the on-call urology team. This requires that the consultant’s elective activity is reduced or stopped when they are on-call. Streamlined on-call systems should involve alternatives to admission to hospital, such as rapid access clinic appointments, and should enable consultants to contribute to the operative management of emergency cases.

Other aspects of on-call work which are flagged up in the national report include the need to review the workload of consultant urologists while on-call and to look at the care of patients presenting with problems that require complex major surgery in the acute setting. A classic example is the patient who sustains urinary tract trauma during a caesarean section, with the resulting call to the on-call consultant who may not, in their day to day working practice, undertake any major open surgery, let alone undertake difficult reconstructive surgery in the pelvis.

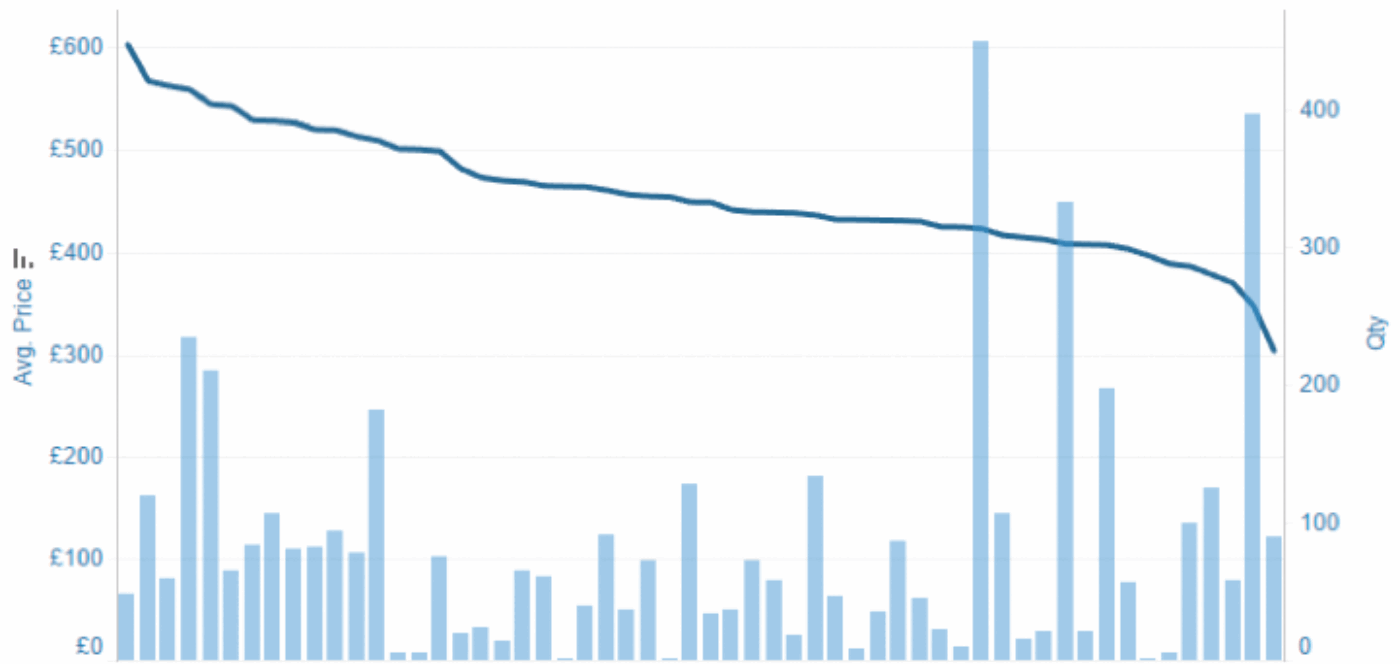

Figure 2: Material costs for a standard endoscopic procedure to treat a ureteric stone, involving the use of two guidewires, a laser fibre, a stone retrieval basket and a ureteric stent. Data is included for trusts for which procurement costs are available for all of the individual items of equipment. The line indicates the total cost of the procedure by trust with the bars representing the volume of procedures per trust.

We all have a responsibility to ensure that NHS resources are appropriately deployed. The work carried out on procurement is of major significance. It is clear that substantial savings could be made by trusts who focus on getting value for money when purchasing urology products. Figure 2 shows that the cost of a stone procedure that utilises a ureteric stent, a laser fibre, a stone retrieval basket and two guidewires varies between £300 and £600 across 56 trusts for whom an estimated cost calculation could be made. There is a need for trust procurement teams to work alongside clinicians in order to ensure that the products which are being used are suitable for the task and appropriately priced.

It is inevitable that concerns will be raised about the quality of data that is collected and which is informing decision-making. It was reassuring that there was relatively little challenge to the quality of data during the clinical visits, which indicated that the data that was being presented had reasonable face validity. However, GIRFT and associated NHS teams, such as the National Clinical Improvement Programme, are working hard to provide support that will help clinicians and trust coding teams to code clinical activity accurately and uniformly. This should mean that future iterations of GIRFT data packs are increasingly accurate as the benchmarking between different organisations steadily improves.

A further area of considerable interest is that of litigation expenditure. Costs continue to increase, along with the number of claims. There is dramatic variation in the expenditure on urological claims from trust to trust. Between 2012 and 2017, the average estimated litigation cost per urological admission was £38, but there are seven trusts for whom that figure exceeds £150. It is important that we learn how to reduce litigation risk. Specific recommendations are made in the GIRFT report.

Implementation: national issues and urological networking

Although implementing many of the proposals put forward in the GIRFT national report will be carried out within individual trusts, some aspects of implementation need to be carried out with the input of a range of organisations. For example, the development of specialist nurse training curricula and, possibly, assessment will need the input of a number of organisations. Reviewing the efficiency and effectiveness of urological cancer multidisciplinary teams (MDT) is already encompassed within a wider review of MDT working. The proposal to alter the standard cancer targets for muscle-invasive bladder cancer and prostate cancer is already under discussion, but will require sign-off from the NHS England Cancer Team.

Much work is already underway, so that discussions are taking place in relation to improving procurement methodology, improvements in the way in that urological data is collected and analysis of information from litigation.

Perhaps the most ambitious recommendation, but also potentially the most important, is the proposal to establish a national arrangement of urological area networks (UANs). It is proposed that a UAN is a collaboration between the urology departments of between one and four hospital trusts. Typically, the population served by a UAN will fall in the range between 750,000 and 1,750,000.

The development of UANs is predicated on the recognition that it is no longer sensible to consider the delivery of urology services on a trust by trust basis. That arrangement worked well in the era when every district general hospital had a urology department, staffed by between two and four consultants, each of whom provided the whole range of urological care. Now that sub-specialisation is well established, it is clear that the majority of individual hospital departments are unable to provide a comprehensive and joined-up urology service. However, a UAN should be able to offer good access to consultant-led acute care and a near-complete range of sub-specialist expertise. The network should be able to make efficient use of expensive equipment, such as lithotripters, lasers and surgical robots.

In order to establish UANs across the country, without the process degenerating into endless boundary disputes, it will be imperative that a comprehensive national model is developed and agreed. Such an approach will mean that all concerned can move forward in the knowledge that there is a settled arrangement across the country for inter-trust collaboration. A first draft for such an arrangement has produced a model with a total of 57 UANs covering England.

It is clear that the country is so diverse in geography and service-demand that imposing a one size fits all arrangement for services in UANs would be doomed to failure. It is therefore expected that clinicians and managers within the trusts that make up an individual UAN will work together to produce a model for urology service delivery which meets local needs. There will be guidance issued with expectations that the model developed will meet the key requirements for high quality service delivery and efficient use of resources. The idea of developing a Service Description Document, which each network would use to set out how their service works, is being considered.

Conclusions

The GIRFT programme provides clinicians with a major opportunity to shape the way that their own service develops. The foundation for GIRFT is clinical engagement, and this has been demonstrated through the independence that has been granted to the GIRFT Clinical Leads in making recommendations about service improvement, the high level of engagement with individual clinicians during trust visits and the enthusiasm for engaging with professional bodies. Both BAUS and BAUN have already demonstrated that they are eager to collaborate with the programme.

As with any process of development, there will be some urology services which move forward rapidly and are in a position to take advantage of the opportunities that are present. Others will face greater difficulties and are likely to make improvements in an incremental way. Finally, there are those where there are major constraints that hamper progress. It will be important to make sure that those services receive the support and encouragement that they will require. It is also important to recognise that a tight funding environment will limit the pace of improvement in areas where money has to be spent in order to move matters forward. However, this problem is offset by the fact that there are considerable savings to be made through increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of clinical services. Regional GIRFT Implementation Teams are available to provide additional advice and encouragement where it is needed.

In my opinion, the GIRFT programme has the potential to facilitate transformational change in the way that urological care is delivered across the country. It is based on sound methodology and is backed by considerable resource. It is hoped that clinical teams will seize the opportunity to use GIRFT as a lever that can be used to improve the care of their patients.

References

1. http://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/urology-report/

Declaration of competing interests: The author is paid by NHS Improvement for work undertaken in relation to the Getting It Right First Time programme.