Writing this article on the first Sunday in May, when in any other year, I would be wearing my bowler hat in Hyde Park for the annual Cavalry Memorial Parade, a time ‘pre-COVID’ does seem a very distant memory. Having served for 22 years in the Army Reserve, much of it spent on exercise in an ‘ops room’, I was approached early in the response and asked to join the hospital tactical command and control cell (TCC).

C3 refers to command, control and coordination; the nomenclature may vary between NHS trusts, but for us: ‘strategic’ has overarching responsibility for the Trust’s response; ‘tactical’ takes a lead on day-to-day issues that need action immediately, and looks at how strategic decisions can be implemented at an operational level; and our divisional operational cells support this in specialist areas including surgery, medicine, women and children’s health, and support services and the community.

The ‘tactical commander’ determines the dynamic plan for the day, the tasks that need to be undertaken to deliver the plan, who will take those tasks on, and monitors progress on the delivery.

Tactical Commander’s Responsibilities – the ‘here and now’:

- What is happening?

- What direction do I need to give to the operational commander now?

- What reporting do I need to arrange?

- Whom do I need to inform?

A Core Resilience Team (CRT) had been established some weeks previously; a multidisciplinary group led by the Trust’s head of performance & efficiency, working alongside the deputy chief operating officer. This talented team was responsible for analysing new Public Health and NHS England (PHE and NHSE) evidence, modelling changes in virus transmission, and producing clinical and logistical operational plans. I spent what I regard as the most useful part of my 17 years as a consultant on a steep learning curve enabling me to become a useful member of the command structure.

How many times as urological trainees, and indeed consultants, have we heard the phrases ‘patient flow’, ‘discharge waiting areas’ and ‘red to green discharge status’, but not fully appreciated these aspects of healthcare? Flow through a hospital is as important to its day-to-day functioning as any robot or hi-tech piece of equipment. My day spent shadowing the patient flow team, who run the crucially important bed meetings four times a day, was one of my most useful educational experiences and I would recommend this to all clinicians to understand how your hospital functions.

Figure 1: Decision making tool.

I was privileged as a clinical lead in a relatively small specialty to be invited to attend the daily strategic briefing, which was chaired by the Trust’s strategic commander, and soon moved from a traditional to a virtual based meeting to comply with social distancing. The CRT prepared proposed clinical and logistical changes and has responsibility of presenting these recommendations for discussion – at West Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust we use an adapted decision model utilised by the police. Figure 1 shows the model used based upon the Joint Decision Model developed by the Joint Emergency Services Interoperability Principles (JESIP).

It was important to find a balance of material that remained both relevant to the strategic level and also included enough information, either verbally or on the slide, to explain the rationale for taking any significant decisions. This meeting set up the day for the CRT, who produced solutions to problems and, via operational and clinical sub-groups, produced the operational plan.

The communications team is an integral part of any organisation; preparing and delivering information concerning the multiple new ways of working both internally and externally, so that colleagues have the information required to remain safe at work. The ongoing challenge of PPE (on this particular occasion, surgical scrubs), the focus on robust and appropriate staff risk assessments, and the ethics of reinstating home birth options for pregnant mothers were just some of the areas that required careful reflection.

After a fortnight, the decision to move towards formalised incident control was agreed, providing 12 hours of on-site cover, the initial model allowing for 24/7 resident cover. The working day started at 07.30 and finished at 20.00; like many rotas during the COVID pandemic, weekends became irrelevant and a day of rest following shifts totalling 50 hours in the control cell was a welcome relief.

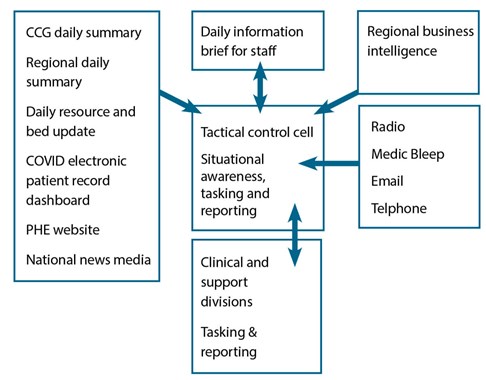

The daily ‘battle rhythm’ consisted of a morning briefing to the strategic team which led to our day’s tasks, some of which were passed onwards to the clinical divisions. Projects were worked on throughout the day, and the divisions reported back to tactical command at 16.00. Across the day, updates are received into a single point of contact email, from clinical commissioning group colleagues and fellow providers to national and regional NHS England guidance. The concept of a generic email works very well as it allows a rapid response to new information and multi-tasking to take place within the team on duty (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Information management.

As the pandemic progressed, the tactical command cell increased in size with senior nursing representation, regular input from estates and resources, and even a ‘fit testing’ rep. What is fit testing? PPE, which includes a variety of FFP3 masks, is procured nationally and pushed into the organisation. A number of different mask models are available, and NHS trusts need to ensure that the mask is fitted to each staff member correctly; there are a few ways of doing this (some with inhaled sprays and some without), but it’s a vital role. Some face shapes don’t fit well with certain masks and a fit testing rota that ran until 23:00, seven days a week was required.

At the time of writing, we are only a few months into one of the most complex changes in the provision of healthcare this country has experienced. Will this crisis be a trigger point for a move to management in the last third of my career? Only time will tell…