In this series of articles I am going to show you some of the exhibits contained in the Museum of Urology, hosted on the BAUS website (www.baus.org.uk).

We often talk about urology being the oldest surgical specialty and discuss the Ancient Hindu, Greek and Roman surgeons and later men such as William Cheselden, Felix Guyon and Sir Henry Thompson being early or proto-urologists. But who was the first urologist? One candidate is the Spanish surgeon Francisco Díaz (1527–1590) so I have asked my friend and fellow EAU history office member Javier Angulo to tell us more.

Francisco Diaz was an eminent doctor and urologic surgeon of the Spanish renaissance during the time of the galenic humanist movement that took place in 16th century Spain known as ‘The Century of Gold’. This was a result of the ruling continuity brought by the Catholic monarchs, Elisabeth of Castille and Ferdinand of Aragon, their grandson the Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire and I of Spain, and their grand-grandson King Philip II. This continuity and the unification of the country and the discovery of America in 1492, at a time of great political instability and struggle over the rest of Europe and the UK, allowed the Spanish monarchy to build a huge economic and cultural empire. This was the period of the great Spanish literature of Cervantes, Lope de Vega and Francisco de Quevedo; but also of equally impressive medical writers such as Francisco López de Villalobos, Luis Lobera, Francisco Vallés, Dionisio Daza, Bartolomé Hidalgo, Andrés Laguna and Francisco Díaz, to name just some of the important galenic humanists of a period when Castilian surpassed Latin as the official language promoting the Spanish Empire.

Figure 1: Visage of Francisco Díaz in a medallion in the cloister

of the Royal College of Surgeons San Carlos, Madrid.

The importance of Francisco Díaz resides in the fact that he was an academic doctor, not an empirical surgeon, dedicated to treating diseases of the urinary tract and to promoting the medical education of physicians, surgeons and barbers in this field. He was born in Alcalá de Henares. Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, confessor of Elisabeth of Castille and later delegate Spanish ruler before the arrival of Charles V to Spain, transformed Alcalá into one of the most important European university cities during the 16th and 17th centuries. Francisco Díaz, the son of a merchant, studied in the university of Alcalá. He became Bachelor of Arts in 1548 and of Medicine in 1551, and doctorated in 1555 (Figure 1). He was appointed Professor of Philosophy, a study superior to Medicine, and took part in the board of ‘Doctors, Masters and Regents’ of the university between 1556 and 1558.

He was married to María de la Flor Medrano, with whom he had six children. After his medical degree, he travelled to Valencia with Luis Collado and Pedro Ximeno, both disciples of Andreas Vesalius, to learn the art of medical dissection. He aimed to get an appointment as Professor of Anatomy in the university of Alcala, but this post was offered to Luis Collado instead. Realising the difficulties of promoting himself in Alcalá and building a fruitful surgical activity in a city with plenty of empirical barber-surgeons (one of whom was Rodrigo de Cervantes, father of the author Miguel de Cervantes), he decided to leave Alcalá. He again failed a contest for surgeon to the court hospital in Valladolid, losing out to Dionisio Daza, who had served in the army of Charles V with Vesalius, however, he did then secure the position of City Surgeon with the Council of Burgos in 1559, to practise surgery in Hospital de la Concepción. Burgos was an important city of 12,000 that dominated the export of wool from Castille to the Flemish territories, at a time when the war had suspended all commerce with the British Islands. The artistic and economic development of the city was however truncated by a terrible bubonic plague epidemic in 1565. Díaz’s wife and youngest daughter died of plague and he decided to return to Alcalá.

One year later, he married Mariana de Vergara with whom he had three more children. His service in Burgos and his friendship with Cristobal de Vega and Francisco Vallés, both professors in Alcalá and doctors to Philip II, secured a position for Díaz with the King in 1568. Thanks to his great knowledge and ability to treat urinary diseases he was conferred the title of Surgeon to his Majesty in 1570, a position he held until he died in 1590. With the privilege of being court doctor, Díaz published his first book in Madrid in 1575, Compendio de Chirurgia based on the dialogues between a doctor and a medical empiric who wanted to understand the principles of surgery. His teaching strategy is evident throughout the book, written in four parts: anatomy, swellings (apostema), fresh wounds and old sores (ulcers). The book presents hospital practice of his time and many tips on how a surgeon with a religious background and full respect to human suffering must behave. The book is a beautiful humanistic work published in vernacular Spanish language, but contains no reference to urologic knowledge except for the anatomy.

Figure 2: First page of Tratado nuevamente impresso de todas las enfermedades de

los riñones, vexiga y las carnosidades de la verga y urina, printed in Madrid in 1588.

His dedication and experience to the diagnosis and treatment of renal, bladder and urethral disease was completely reserved for a second master work, also in Spanish, entitled Tratado nuevamente impresso de todas las enfermedades de los riñones, vexiga y las carnosidades de la verga y urina, dividido en tres libros [A newly printed treatise on all diseases of the kidneys, bladder, fleshiness of the penis and urine, in three volumes] (Figure 2). It was printed in 1588, the year of the Armada. The first book describes sands, stones, inflammation and other renal diseases; the second one is about sands, stones and sores in the bladder and the third one, the most innovative, presents a very practical perspective on fleshiness and calluses in the exit of the penis. Díaz uses more than 1000 medical terms in old Spanish of which approximately one third are newly used, most of them invented by him as he translated from Latin and Greek. Interestingly half of the new terms he applies are still in use today in modern Spanish.

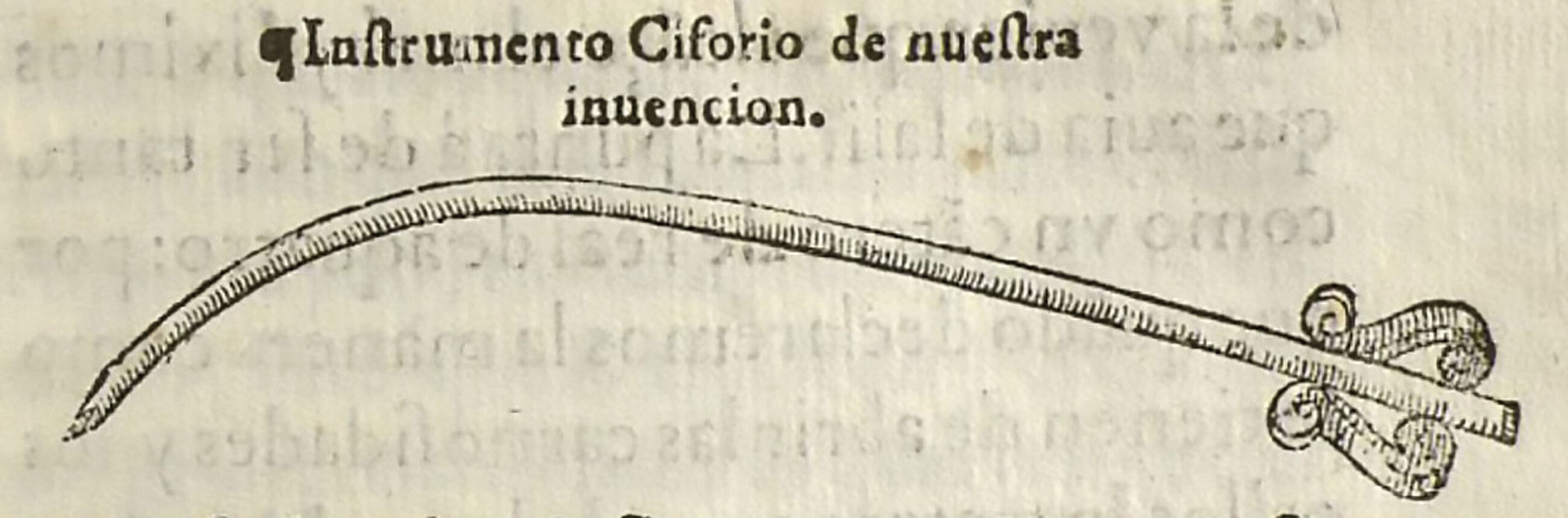

Figure 3: Detail of the scissoring instrument, used as the first urethrotome.

The title, A newly printed thesis... has led to speculation that there could be a first copy of the book not yet discovered. This is highly unlikely; Díaz mentions a book on anatomical dissection he wrote and another on bubonic plague he was about to publish, but neither of them have been identified. Several surgical instruments presented are of his own invention; like the modified civet with a cutting point (scissoring instrument) that he used to perform blind urethrotomy (Figure 3), for use when “candles covered with a flesh-eating ointment” (caustic bougies) failed to treat urethral fleshiness (strictures or possibly obstructing prostatic tissue). When describing the cutting of the stone he presented many instruments beautifully depicted. Although he followed Marianus Sanctus classic description in De lapide, published in 1540, he controversially claimed that lithotomy was not an Italian, but a Spanish invention.

Francisco Díaz has been compared to the famous French surgeon Ambroise Paré (1510–1590) due to their time frame, for using woodcut prints to represent surgical instruments and in their descriptions of how to perform interventions. However, Díaz was not a practical surgeon like Paré, he was much more a philosopher and scholar. His books are very humanistic, with many anecdotes of famous characters including emperor Charles V and his noblemen. He described, for example, how he performed the autopsy of his respected professor of Medicine Fernando de Mena who died in 1585 of sepsis due to an embedded stone.

The knowledge of Díaz regarding botany and pharmacy is immense and his books are full of references to Classical and Arabic authors. He really tried to establish a career of academical dedication to the treatment of urinary diseases. Díaz was a pious man, very careful not to provoke envies within his medical colleagues. He participated as witness in an inquisitorial process held against Eleno de Cespedes, a transgender surgeon in Toledo to which Díaz was exculpatory in his expert report despite this putting his own life in danger. What is more, Díaz was himself a poet and friend of Lope de Vega and Miguel de Cervantes (author of Don Quixote), the latter calling him ‘Spirit of Apollo’ in one of his laudations.

In Spain, the Francisco Díaz medal is the most important award given every year by Asociación Española de Urología and Francisco Díaz has been studied by many scholars, although not enough in non-Spanish languages. With his fine 1588 publication, he can reasonably be considered to be one of our first urologists.