Penile implants are inert objects placed beneath the skin of the penis through an incision. These are variously referred to as Yakuza beads, pearls, ball bearings, speed bumps, penile marbles, inserts, etc. The term ‘penile implant’ described here should not to be mistaken with the therapeutic inflatable or semi-rigid implants used for the surgical treatment of erectile dysfunction.

In the context of this article, the primary aim of inserting implants is to increase sexual pleasure for both partners during intercourse and for a more intense orgasm by producing enhanced friction. The implants do have a similar effect to that of ribbed condoms and have received mixed reviews by women [1]. The implants are also sometimes thought to increase penile aesthetics [2]. It has been found that there may be multiple factors influencing the decision to have an implant inserted including: cultural backgrounds, peer influence, affiliation to a certain group, demand from female sexual partners and as a symbol of manhood and potency.

There is a 20-fold rise of men in the UK requesting penile fillers to increase the girth of their penis by injecting hyaluronic acid (more commonly used in facial aesthetic treatments), according to lay media reports [3]. Hyaluronic acid injections are a different technique to insertion of pearls, but the principle behind the process of increasing sexual satisfaction is similar. It therefore means that, although the practice of inserting penile pearls is not a very common practice here in the UK at present, it may become more common in the near future as men seek to find more innovative ways of exploring and ensuring sexual satisfaction.

History and incidence

Inserting implants in the form of beads or pearls into the penis to enhance sexual satisfaction, has been gaining popularity in both the developed and developing world. In some countries it is particularly common in young men in the military and amongst sailors and convicts [4]. Whilst nowadays men are choosing to insert the pearls for sexual satisfaction, the practice is said to have originated in Asia with members of Yakuza (a transnational crime syndicate) performing pearling during their time in prison. One bead was inserted each year to symbolise the time spent behind bars [5]. By making, polishing and subcutaneously inserting the implants in the foreskin, prisoners combatted the boredom felt in prison and also gained an income by selling and then performing the actual procedure [6].

The implants were traditionally reported among men of Asian and Slavic origin, but more recently the practice has gained increased popularity in the Americas especially in the Caribbean islands. Case reports and studies of prisoners and ex-prisoners in Eastern Europe, the United States, Papua New Guinea and Indonesia suggest that this population may be gradually adopting the practice [2]. According to a report published in January 2013, based on a survey conducted by Lorraine Yap et al. in 41 prisons in New South Wales and Queensland, Australia, 73% of men who had penile pearls from the 2018 prisoners surveyed had it done while in prison [7].

Procedure

The implants are made of a wide range of material including glass, marble, plastic, wood, metal and silicon. Unfortunately, the procedure is most commonly done in illicit settings outside of medical centres, therefore making it almost impossible to adhere to antisepsis and aseptic protocols. Increasingly in the Americas, given the growing frequency of the practice, some doctors are more open to the concept of inserting the pearls for patients who wish to have it done in a safer and more sterile fashion.

In prison where it is done most commonly, and additionally most studies have been conducted, toothbrushes, dominos, dice, melted toothpaste caps and deodorant roller balls are the most routinely used objects. The procedure of actually placing the implants is quite simple and is done without any form of analgesia. The penile skin is penetrated using an object with a sharp point and the implant is pushed under the skin through the small incision made until it occupies the desired location. The implants may be inserted in any part of the penis but it is most commonly found on the dorsum of the shaft or the foreskin [4].

Figure 1: Image showing loose attachment of the penile skin to the fascia beneath.

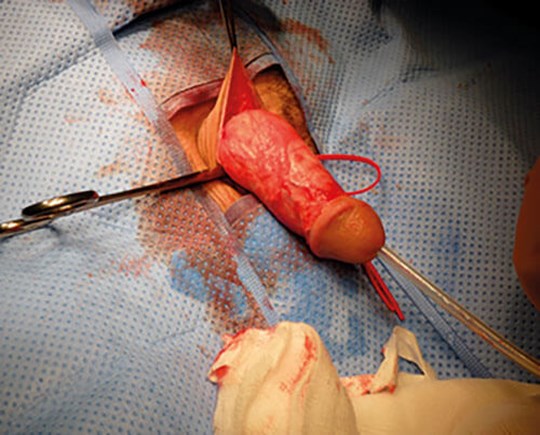

As the penis is covered by thin and mobile skin which is attached very loosely to the tissue beneath (Figure 1), the implants can be slid into position. The fact that the objects are not fixed contributes to their motility in the subcutaneous tissue offering the desired sexual results (Figure 2). The wound is left to be closed by second intention. The procedure is done by the individual himself or by a designated non-medical provider such as a particular convict who has gained experience of inserting the objects.

Figure 2: Image showing artificial pearls in the penis.

Complications

It goes without saying that no surgical intervention is free of the possibility of experiencing complications. However, it is understood that when artificial penile pearls are inserted without adhering to the correct aseptic measures, the chances of complications increase significantly. The complications associated with penile pearls are not only restricted to the actual procedure of inserting the pearls, but the long-term effect of having them in place [4]. Although data is scarce regarding long-term complications, one study has shown that 96.6% of 60 interviewed implant bearers had no complications eight years after implantation.

This is probably because the true incidence of early or delayed complications is likely to be underreported, given the circumstances of the practice. One of the most frequently recognised complications is infection. This would be expected to be more prevalent when the procedure is done outside of a medical facility, without use of sterile techniques. If an individual presents with an established infection, the implant should be removed to enable treatment with antibiotics as required. On a few occasions, deeper infections with abscess formation have been recorded.

Because there isn’t much data about the procedure taking place at medical facilities or by medical professionals, comparison of infection rates between the two groups of patients is impossible. One can only assume however, that there will be a significant difference due to the appropriate measures being put in place to prevent possible complications.

Prisoners are at increased risk of contracting blood borne viruses arising from blood to blood contact during injecting drug use, tattooing and violence. Penile implantation may increase the transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), amongst other sexually transmitted infections and blood borne viruses. Inserting the implants in prison in most cases involves the use of shared non-sterile gloves, sharp instruments used to make skin incisions, and direct contact with other people’s blood [8].

Despite the common claim that the penile inserts increase a partner’s sexual pleasure, the Journal of Sexual Medicine found that there is little evidence to support this claim. There has been mixed feedback from partners of men who have penile implants [1]. It has been compared to ribbed condoms in terms of increased sexual stimulation by some, while others have described significant dyspareunia. There have been reports of vaginal bleeds, ulceration, and other injuries to the vagina and cervix which predisposes their partners to infections [9]. Other concerns voiced by the women surveyed were the threat of unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections due to condoms being less likely to fit and more likely to break. Men with penile implants are less likely than other groups to use condoms during intercourse mainly because of the ‘machoism’ associated with having the implants.

Other less frequently reported complications associated with penile implants include painful erections, erythema, swelling, rejections, functional impotence, urethral stenosis and well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the penis. The exact mechanism by which the implants cause SCC of the penis is not known but it is believed that the penile nodules provoke local and repetitive trauma that can elicit chronic inflammation, which can play a role in the pathogenesis of carcinoma.

Some literature has also attributed it to the increased risk of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection as a result of the increased risk factors stated earlier [10]. It has been proven that epidermoid carcinoma can be caused by mutilating circumcision scars. Men with penile lesions deriving from these scars due to the insertion of pearls can have a four to six-fold elevated risk of developing SCC of the penis [1].

One such case was reported by Thiago Teixeira et al. in the Journal of Surgical Case Reports where a middle-aged man was diagnosed with a penile lesion and bilateral lymphadenopathy [11]. He underwent a penectomy and histology confirmed epidermoid cancer which had infiltrated the glans, coronal sulcus, foreskin, corpora cavernosa, corpus spongiosum, and penile urethra.

A granuloma formation is a natural host response to seal off exogenous substances with inflammatory cells. This phenomenon can occur with artificial penile implants which leads to a firm disfiguring subcutaneous mass, which if very severe can lead to erectile difficulties and cosmetic issues.

A recent systematic review concluded that the low prevalence of various complications in both men and their partners is likely to be consequent to underreporting [5].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually straightforward and the hardness of the implanted beads is pathognomonic. These objects are usually palpable as mobile non-tender, hard subcutaneous nodules and when followed with details of clinical history shouldn’t pose any problems for the Urologist. However, these may cause diagnostic confusion in certain patients if they are associated with genitourinary complaints. In cases where an MRI scan has to be done, having the pearls in place can hinder such investigations depending on what form of materials they are made up of or if the nature of the material is unknown.

It is worth mentioning that injecting different oils into the penis for increasing girth can also produce granulomas and one should be cognitive of that. Differentiation between the causes can be by recognising the diffused nature of the granuloma due to injected materials as opposed to being confined in pearls.

Conclusion

In recent times, body modification has become increasingly popular and healthcare practitioners need to be aware of the different forms and associated complications which may arise. One such practice is the insertion of artificial penile pearls discussed in this paper. Although the practice was initially initiated as a symbol marking the length of stay in prison by some Asian groups, the focus of its primary use has shifted considerably to increase sexual stimulation and pleasure. The practice remains most prevalent in prison but increasingly other groups of men in society are adopting the practice. There are significant gaps in the available evidence about the rate of complications associated with the practice. What we do know is there can be a wide range of complications from wound infection and abscess formation, to sexually transmitted infection, injury to partners, and even malignancy.

References

1. Kamenez M. The problem with DIY penis implants. The Atlantic 2013

www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/

2013/02/the-problem-with

-diy-penis-implants/272766/

[accessed 26 March 2019].

2. Edlin RS, Aaronson DS, Wu AK, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma at the site of a Prince Albert’s piercing. J Sex Med 2010;7:2280–3.

3. Kelsey R. The men having penis fillers to boost their self-esteem. BBC News 2018

www.bbc.co.uk/news/

health-45735061

[accessed 26 March 2019].

4. Wilcher G. Artificial penile nodule – a forensic pathosociology perspective: four case reports. Med Sci Law 2006;46:349-56.

5. Flynn RM, Jain S. A domino effect? The spread of implantation of penile foreign bodies in the prison system. Urol Case Rep 2014;2:63–4.

6. Kelly A, Kupul M, Nake Trumb R, et al. More than just a cut: A qualitative study of penile practices and their relationship to masculinity, sexuality and contagion and their implications for HIV prevention in Papua New Guinea. BMC Int Healh Hum Rights 2012;12:10

7. Yap L, Butler T, Richters J, et al. Penile implants among prisoners—a cause for concern? PLoS One 2013;8(1):e53065.

8. Loue S, Loarca LE, Ramirez ER, Ferman J. Penile marbles and potential risk of HIV transmission. J Immigr Health 2002;4:117-8.

9. Kakinuma H, Miyakawa K, Baba S, et al. Penile cancer associated with an artificial penile nodule. Acta Derm Venereol 1994;74:412-3.

10. Hudak SJ, Mcgeady J, Shindel AW, Breyer BN. Subcutaneous penile insertion of domino fragments by incarcerated males in southwest United States prisons: a report of three cases. J Sex Med 2012;9:632-4.

11. Teixeira T, Souza G, Campos R, et al. Penile cancer in patient with a ‘Bouglou’ penile adornment. J Surg Case Rep 2014.

Acknowledgements

Mr Christy Daniel, Consultant Urologist, Victoria Hospital, St Lucia and Ms Arlette Charles, Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, Victoria Hospital, St Lucia.